The Tromsø and Norwegian Sealing and Whaling Industries

The Arctic Hunting Boom

Introduction and Summary

What was the Arctic Hunting boom? It was the rapid exploitation of seal, whale and Arctic and sub-Arctic fisheries. Arctic hunting took off in the early 1800s and was stimulated by the growing urbanisation of Europe and increasing demand for whale and seal oil/fat for a wide range of uses.

It seems that Tromsø was a key port in this trade but so far I have been able to discover very little about it.

Broadly speaking it seems that large scale commercial whaling developed in far Northern Norway for a period before being outlawed due to fishing community protests. It then moved offshore but was carried out and financed by Norwegian companies. But I have also come across a set of photographs of whale processing in the National Library of Norway that seems to show this activity being carried out in Tromsøsund (Tromsø Sound) in the early 1960s (see Whaling section below).

Tromsø is more implicated in the sealing industry and was a base for it. And an important consequence of sealing was that it allowed hunters and merchants to accumulate the fund to finance a shift into whaling (see Kalland in in Whales, Seals, Fish and Man, 1995).

Continued Harp Seal hunting is extremely controversial because all the hunts (Russia, Norway and Canada) except Greenland (which kills overwhelmingly one year-plus seals) focus on killing seal pups at the 'beater' stage (that's when they start to beat their flippers) when they are over 18 days/3 weeks old and have been weaned and abandoned by their mothers and lie helpless on the ice sheet until they can swim at 7-8 weeks.

There is also controversy about killing methods (rifles are used in Norway) and tests for 'deadness' prior to skinning.

In Norway, where Barents Sea cod stocks have not collapsed (as opposed to Newfoundland where they appear to be gone forever) hunting quotas (which have not been anywhere near used in recent years) are allocated in relationship to keeping the Harp seal population at a level where it will not overly harm cod and other stocks by predation - particularly the capelin - which is an important food source for the Atlantic Cod (see my related page on the Arctic Norwegian fishing industry).

At the same time the Norwegian policy seems to be to want to drive seal hunting by making it commercially profitable, which it is not in Norway for a number of reasons, the outstanding one being (in comparison to Canada) the distant location of the breeding seal stock in the White and Greenland Seas. (See here for the Norwegian government line of 2001 and a new regulation in 2005 to allow foreigners to shoot seals here.)

If the Norwegian state instigated a seal cull instead of using a dying commercial sealing industry as a proxy this would seem to make more sense if the seal/fish-stock nexus is proveable. This cull would then presumably focus on mature seals as a way of controlling herd size - rather than pups.

It raises its own difficulties in that Harp seals are mainly pelagic - out at sea - and mainly underwater. Killing mature males and females during ice-based courtship prior to in-water mating (which occurs after the females have weaned their pups at 12 days) or in the open-sea would be pretty hard and resource intensive.

But if the fish stock is really under threat (see below for Harp seal invasions of the North Norwegian fisheries) from the Harp seals maybe this is a price worth paying.

I can understand how 'little' Norway doesn't want to be pushed around by the EU (which has banned seal products), the WTO (which upheld the EU ban), North American and European public opinion and anti-hunt NGOs . And I can understand that it may feel some sense of solidarity with Canada and its seal hunt (the Greenland hunt is very different) but from what I have read continuing the Norwegian hunt for Harp seal pups makes little economic or moral sense.

It is true that since the increasing regulation of the veal industry many bull calves are shot at a tender age but this is because they are a by-product of the dairy industry and not as a way of culling the herd in general. It is deplorable but hopefully it is quick and humane and fits into the economic logic of an industrialised method of farming.

Killing Harp seal pups at an economic loss with the justification of effectively culling the North East Atlantic Harp seal population to protect cod stocks just does not make sense. At least to me. And maybe climate change will do the job for the Norwegian state. In 2011 deteriorating sea ice conditions in Canadian waters are thought to have led to the loss of 80% of Harp seal pups.

See this from Arkive.com which has the best profile of the Harp Seal (Pagophilus groenlandicus),

Global warming poses the biggest threat to the harp seal , as it requires pack ice for moulting, breeding and resting. As temperatures rise, pack ice is becoming less extensive and does not remain frozen for as long, reducing suitable habitat for the harp seal .

In December 2014 the Swedish parliament voted to end state subsidies to the Norwegian seal hunt: 'A majority of lawmakers voted late Thursday to delete a 12-million-kroner (1.3-million-euro, $1.6-million) subsidy for the seal hunt from the 2015 budget'. This amounted to 80% of the revenue of the seal hunt and on a catch of 12,000 seals would equal a per head subsidy of NOK 1,000 (c. £100) per seal. The IFAW claimed that only three boats took part in the 2014 Norwegian hunt.

The Tromsø Sealing Fleet 1859-1909

The Tromsø fleet increased almost eightfold, from 6 vessels in 1859 to 46 in 1909 while the harvest of seals increased from less than 1,500 to over 30,000 animals annually. The geographical range of the hunting grounds expanded correspondingly from a limited area around Jan Mayen and the west coast of Spitsbergen to a huge area which included the western ice (north and south of Jan Mayen), the northern ice (Svalbard), the eastern ice (Kola Peninsula to Novaya Zemlya, the White Sea), Zemlya Frantsa-Isoifa [Franz Joseph Land], the Denmark Strait and northeast Greenland. ... Owners and skippers responded to reductions in numbers by searching for new hunting grounds and, in doing so, sailed further north, then east and then west than ever before, coincidentally making a series of historical voyages of discovery. By the end of these five decades sloops had largely been replaced by ketch rigged diesel sealers, these being an assortment of new, salvaged and second hand foreign ships.

From Kjær, KJ. Serial slaughter: the development of the north Norwegian sealing fleet: 1859–1909, Polar Record 2011 47/1.

Harp Sealing

The Herds

There are three main herds of harp seals: the Barents Sea herd which migrates to the White Sea, north of Russia; the East Greenland herd which migrates to Jan Mayen Island, southeast of Spitsbergen, Norway, and the Northwest Atlantic herd which migrates from Baffin Island to the east coast of Newfoundland & Labrador and to the Gulf of St. Lawrence.

History

The following is an extract from the First Norwegian Submission of 9 November 2012 to the WTO Case: European Communities – Measures Prohibiting the Importation and Marketing of Seal Products First, pp.12-13. The WTO upheld the EU ban on the import and sale of seal products.

The British and Dutch originally dominated the commercial sealing industry in the North Atlantic from around 1700 and the Norwegian involvement did not commence until the late 18th century. From the first half of the 19th century Norwegian commercial sealing became an important industry providing substantial profit and considerable employment.

Harp Seals are hair (as opposed to 'fur' seals) and 'have been used for their pelts, their flesh, and their fat, which was often used as lamp fuel, lubricants, cooking oil, a constituent of soap, the liquid base for red ochre paint, and for processing materials such as leather and jute.'

The hunt focused primarily on Harp and Hooded seals, and the hunting grounds were the three whelping areas known as the “West Ice” around the island of Jan Mayen, the White Sea, and Newfoundland. After World War II the Soviet Union banned Norwegian sealers from the White Sea, but Norwegian sealing continued in the “East Ice”, i.e. in the Barents Sea north of the mouth of the White Sea. The considerable Norwegian seal hunt in Newfoundland came to an end in 1982.

Peak Years

The seal hunt peaked between 1921-25, when more than 200,000 animals were caught annually, and in 1959, when 67 vessels landed almost 300,000 seals. On average around 40-50 vessels participated in the yearly hunt in the West Ice from after World War II until the 1960s. The seal populations in the East Ice and West Ice could not withstand the large-scale seal hunt that had been established between the two world wars and catches have therefore been regulated by quotas since the 1970s, leading to the re-growth of all three populations of harp seal. The harp seal population in the West Ice is now the largest on record.

Products

Fur, skin and blubber have traditionally been the commercially most important products. The blubber was boiled to obtain oil for industrial use, both for soap and margarine. The meat has been regarded as a local delicacy. In the 1990s, development of Omega 3 fatty acids from seal oil for human consumption began.

Locations

The Norwegian seal hunt takes place each year between 10 April and 30 June when harp seals gather in their traditional whelping [birthing] areas. The hunt mainly takes place in the drift ice areas north of the island of Jan Mayen, east of Greenland known as the “West Ice” ... Hunting also takes place, to a lesser extent, in the areas east of 20ºE in the Russian Economic Zone known as the “East Ice”.

(WTO Case: European Communities – Measures Prohibiting the Importation and Marketing of Seal Products First Norwegian Submission 9 November 2012 pp.12-13

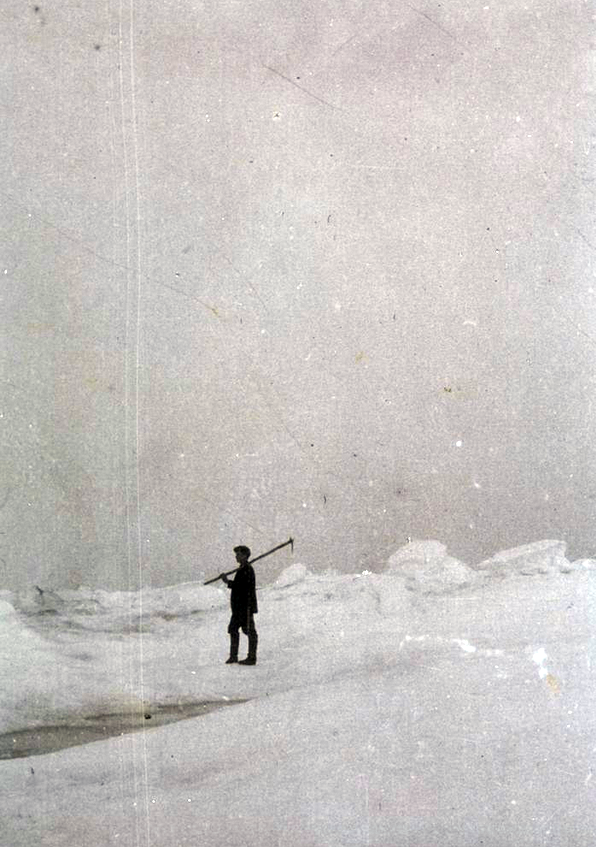

Kill Methods

Seals are either shot from boats on the mainland and islands or caught on pack ice and shot and finished off or killed with a hakapik (a club and gaff type hand-tool) by certified seal-catchers (fangstmenn). The seal hunt appears to be highly regulated and in decline. In fact it is subsidised by the state as the return from seal products - primarily skins - does not make it economically viable.

Lindberg Case

See here for the so-called Lindberg case when a journalist accused sealers of illegal practices in 1988 after accompanying them on the sealing boat, Harmoni. The case eventually went to the European Court of Human Rights.

The court ruled by a majority decision in favour of freedom of expression versus defamation claims. The case made the international media when Lindberg made a film including footage he had taken whilst on the board the Harmoni. The incident was illustrative of the controversy and passions involved in the continuation of sealing in Norwegian waters.

Quota and Herd Size

In 1950 255,000 seals were taken in Norwegian waters. In 2011 there was a quota of 49,400 but only 7, 673 seals were taken, the majority of which were Harp Seals.

There are 'almost three million [seals] in the areas where Norwegian sealing takes place. Stocks of both species [Harp and Hooded Seals] are growing' according to this Norwegian government website. It goes on to say,

The daily energy requirement of a harp seal is equivalent to two and a half to three kilograms of herring or capelin. The large seal stocks are making heavy inroads into stocks of various fish species, including some that are used for human consumption.

And at times the unchecked growth of seal stocks has 'resulted in massive seal invasions along the Norwegian coast' with damage to fish stocks and equipment.

Harp Seal Invasions

In February-May 1987 huge numbers (est. 300-400,000) of Harp Seals moved to the coast of Finnmark, Troms and Nordland. 56,000 were caught in gill nets as by-catch and a bounty claimed on them that was provided by the government. Estimates of total gill net deaths are 100,000.

Seal invasions have occurred periodically and are poorly understood but seem to be linked to exceptional cold and sea ice cover. But they usually last for one or two years. This changed recently and invasions persisted throughout the period 1978-1994 with varying intensity.

A more likely explanation than cold winters - which were not consistent in the 1978-1994 period - is lack of food. In the late 1960s the Norwegian spring spawning herring population collapsed and has only slowly recovered. And in the 1980s the capelin population collapsed to briefly recover and again collapse in the early 1990s.

See Haug and Nilsen in Whales, Seals, Fish and Man (1995).

Competition for fishing resources

The combined East and West Ice population of Harp Seals in the North East Atlantic and Barents Sea is estimated at 2.7 million (2005-7). There is a much smaller population of Hooded Seals

(67,000).

The annual food consumption [of North East Atlantic Harp Seals] was estimated to be within a range of 2.69 - 3.96

million tonnes of biomass. Distributed across a representative mix of prey species, point estimates

of 1.22 million tonnes crustaceans, 808,000 tonnes capelin, 605,000 tonnes polar cod, 212,000

tonnes herring and a mix of gadoids and other more Arctic fishes of ca 500,000 tonnes were

obtained.

Prospects for future sealing in the North Atlantic - Proceedings of the 13th Norwegian-Russian Symposium Tromsø, 25-26 August 2008, Pike, D., Hansen, T. and Haug, T. (eds) Institute of Marine Research, Tromsø 2008, p. 12.

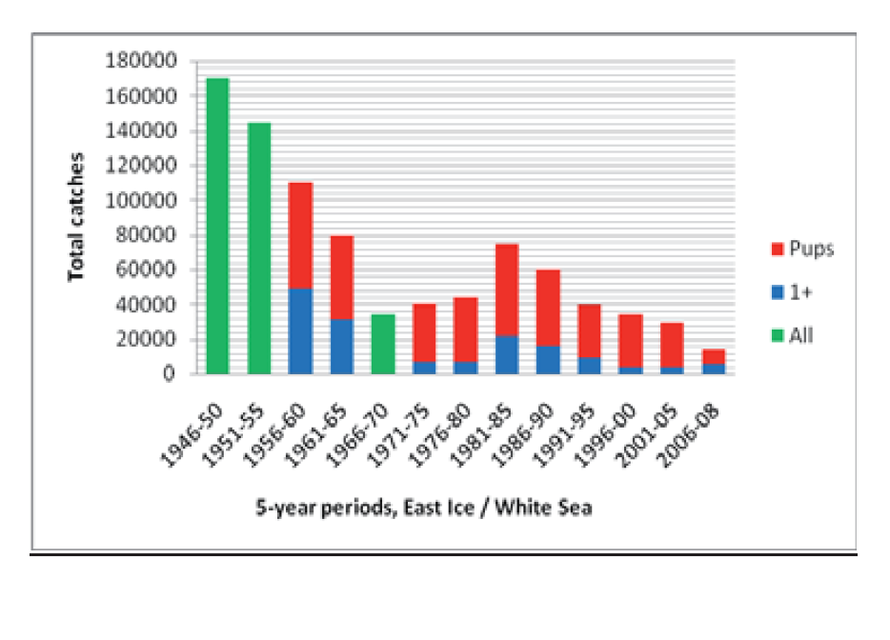

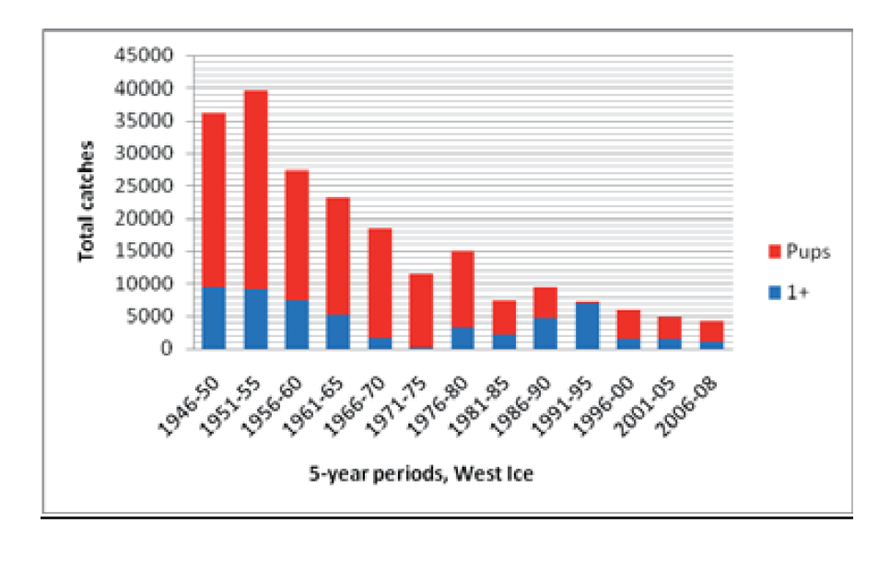

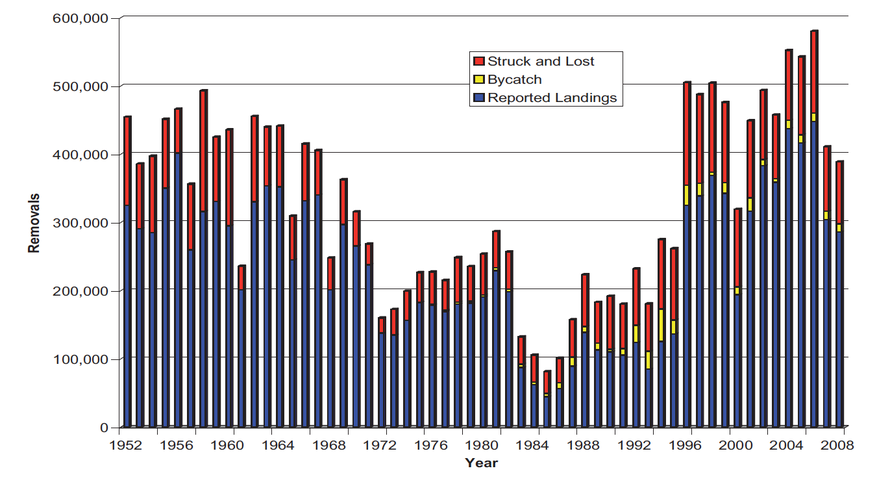

The Post War Norwegian Seal Harvest

The two diagrams below for the Harp Seal 'take' in the East Ice/White Sea and West Ice areas of the Arctic Circle dramatically illustrate the problem that confronts the sealing industry's public profile. It is one thing to argue that some form of culling is required to manage wild Harp Seal stocks vis-a-vis their predation of fish stocks in the North East Atlantic and Barents Sea. But it is another to do this by largely culling pups for their pelts rather than culling mature breeding males.

It is argued - see the introduction by Jørn Krog, Secretary General, Norwegian Ministry of Fisheries and Coastal Affairs to the Prospects for future sealing in the North Atlantic Symposium 2008 for example - that urban dwellers are removed from the deaths of the animals they happily eat - although the veal issue is interesting here - and that this should be no different for the killing of seals. But if farmers went about clubbing calves to death (an awful lot of bull calves are now shot) this might change.

There seems to be a real mix-up in the arguments for sealing. It is argued (see preface to the Symposium below) that in order for the cull to work it has to driven by commercial imperatives - selling seal products.

The main objective of the Norwegian sealing policy is to make possible a profitable

development of the sealing industry.(Symposium p. 31).

But not much of the product is saleable and increasingly markets have been closed to seal products.

The most saleable product is seal pup skins (bluebacks) but the killing of pups until they are 'beaters' (18 days plus old - when they are stranded and defenceless on the ice until they can swim at 7-8 weeks having lost half their post weaning body weight of 36kg) has been banned in the Norway sealing industry.

'The skin of adult seals has virtually no value. [Although] there is a good market for fat and meat from seals in Norway, and all the meat from the animals is used. It is salted or vacuum packed and frozen, then sold in the northern regions of Norway.' (Symposium p. 33)

Most Canadian seal skins used to make their way to Russian (Russia banned seal product imports in 2011) and Asian markets, some being processed in Norway. One such company is Rieber of Bergen.

Almost all seals processed by Rieber are beater [3 week +] harp seals. The skins are mainly used with the

fur on. Products made from sealskins today include fashion items such as jackets and vests,

hats, sporrans, shoes and boots, carpets and furniture. (Symposium pp.39-40)

The Harp Seal Economy

At present the total annual harvest of seals amounts to about 400,000, with a primary (wharf) value of 10-12 million USD. The total retail value of all seal products is over 100 million USD.

Knut Nygaard, Director, CGRieberSKINN AS Bergen (Symposium pp.39-40)

Taking the higher figure this results in a per seal wharf value of $30 and a $250 (after processing, manufacturing and distribution) retail value.

Canadian Harp Seal Hunting

The catches in Norwegian/Russian waters are dwarfed by the Canadian Harp seal harvest which rose to 354,867 seals in 2006 before declining due to poor ice conditions and low prices to approx. 200,000 in 2008. (see p. 19). The industry claims that it supports over 6,000 sealers in remote coastal communities who may derive as much as 35% of their annual income from sealing.

In 2006 the value of the [Harp] harvest to the economy was in excess of C$55m in Newfoundland and Labrador alone (Symposium pp.35-7).

Greenland Harp Seal Hunting

Harp Seals are also harvested in Greenland with the catch for 2006 at just over 90,000. The difference here is that almost all those seals taken are 1+ seals - that is over one year old rather than pups. Is this because in Greenland the seals are harvested for meat or hides rather than pup fur?

The meat from the [Greenland] catch is either consumed by the hunter and his family [or fed to sled dogs in Northern Greenland] or sold at local meat and fish markets. The skins are either kept for home use or sold to the Great Greenland Company (Symposium pp. 34-5).

Total Harp Seal 'removals' in the Northwest Atlantic (Canada and Greenland harvests) in 2008 was estimated to be approximately 389,000. This comprised seals landed, seals shot but not landed and seal caught as by-catch in fishing operation (see diagram below).

2007 population estimates of NW Atlantic Harp Seals are 5.5m. (see Symposium pp.18-23)

The economics of the hunt: MS Havsel

The economics of the hunt are terrible.

In 2008 one boat - MS Havsel - out of Alta comprised the 'Norwegian seal hunt'. Between 6th April and 19th May it took 1,250 Harp seals at the 'beater' stage. These were killed by shooting and regulations mean that 'beaters' can only be shot on the ice and not in the water. The catch was worth NOK500 per seal equalling a total revenue of NOK 62,500 (about £6000) for a six-week-plus trip in a 29 metre, 200 tonne ice class boat that had to take shelter twice in Iceland from storms.

Not surprisingly, in 2008 the skipper of the Havsel believed that the Norwegian seal hunt was at an end in 2008 (Symposium pp. 32-3). Although no mention was made here of the sate subsidy for commercial sealing (see below).

(In 2010 and 2013 it looked like the Hasvel was being used as an ice-class expedition ship to go to Svalbard. It may have moved from Alta in North Norway to Korsfjord near Trondheim in 2010. Weirdly, Jeremy Clarkson and a BBC film crew were pictured on board the Havsel in March 2015. They had chartered the boat to get them around Svalbard for a programme they were making on the Atlantic Convoys to Murmansk in the Second World War).

Surely it would be better for the Norwegian government to carry out a state financed and managed cull of the mature breeding Harp Seal population - which is much harder given that it is by whelping (giving birth) on sea ice that the Harp Seals become vulnerable to easy harvesting. The state could then work out what to do with the culled carcasses.

This would seem more honest than leaving the job up to commercial sealers working on low margins who target the most profitable part of the seal population rather than the part that might control the population more effectively. After all, with a life expectation of 30-35 years a female seal can produce say 25-30 pups in a lifetime.

The Harp seal hunts in Canada and Greenland seem to have a better economic position. This may be due to the proximity of seal herds to hunters whilst the Norwegian hunt takes place on far distant ice shelves in the White Sea and Greenland with long steaming times and the need for ice class boats. In Greenland there also appears to be a strong link between local meat and hide consumption and hunting with some state subsidy thrown in.

Are there different regulations particularly with regard to taking 'ragged jackets' (pups at two weeks old) which have the most valuable pelts/skins? It doesn't look as if they are different - even according to anti-seal hunt sites. Until recently the Canadian Coastguard broke the ice to the herds for the hunters but this has now been discontinued.

Subsidies

In December 2014 the Swedish parliament voted to end state subsidies to the Norwegian seal hunt: 'A majority of lawmakers voted late Thursday to delete a 12-million-kroner (1.3-million-euro, $1.6-million) subsidy for the seal hunt from the 2015 budget'. This amounted to 80% of the revenue of the seal hunt and on a catch of 12,000 seals would equal a per head subsidy of NOK 1,000 (c. £100) per seal. The IFAW claimed that only three boats took part in the 2014 Norwegian hunt.

Harpseals. org, an anti-sealing campaign group, states that,

the Newfoundland provincial government has fully subsidized the industry by giving CAN$3.6 million 'loans' to the Norwegian seal skin processor, Carino, to buy pelts from sealer.

The Future Prospects for Norwegian Harp Sealing 2008

The main problem for the sealing industry in the last 2-3 decades has been the market situation. Protest activities initiated by several Non-governmental Organizations in the 1970s destroyed many

of the old markets for traditional seal products which were primarily the skins. The results have been reduced profitability which subsequently resulted in reduction in available harvest capacity

(e.g., the availability of ice-going vessels) and effort. With the present reduced logistic harvest capacity in Norway and Russia it is impossible to take out catches that would stabilize the

stocks at their present levels. Unless sealing again becomes profitable, it is likely that this situation will prevail.

From Prospects for future sealing in the North Atlantic - Proceedings of the 13th Norwegian-Russian Symposium Tromsø, 25-26 August 2008, Pike, D., Hansen, T. and Haug, T. (eds) Institute

of Marine Research, Tromsø 2008, Preface.

Grey and Harbour Seals

The coastal seal hunt, which involves mainly grey seals and harbour seals living in colonies along the entire Norwegian coast, is conducted on a small scale. Yearly quotas are set for population management purposes. The indigenous Sami communities living in northern Norway have a long-standing tradition of seal hunting and are among those who currently participate in the hunt of a small number of coastal seals (Norwegian Submission to the WTO 9 November 2012 pp.14-16)

It seems some seals are protected in marine reserves and are important for Norway's eco-tourism market. At the same time foreign nationals are now allowed to hunt seals as long as they are accompanied by a Norwegian national. this circle is squared by the following comment from the Ministry of Trade, Industry and Fisheries,

This combination of conservation and sustainable use is the core of Norway’s management policy on seals.

The Joint Norwegian-Russian environmental status 2008 Report on the Barents Sea did not agree with these nice words.

Harbour and grey seals are the only two species resident at the Norwegian coast and are 'constant nuisance to the fishermen' and the last host of the cod-worm.

When the abundant harp seals make mass migrations into coastal waters, these conflicts get very intensified. Thousands of seals might drown in gillnets resulting in significant financial losses for local fishermen during these rare events.

In a white paper ... [2004] the Government stated its intention of regulating population growth in coastal seals to reduce damage to the fisheries and problems for local communities.

Stocks of harbour seals and grey seals in Norwegian sector of the Barents Sea are subject to fishery-related mortality and hunting mortality that in combination are

unsustainable. Harbour porpoises are also subject to by-catch in fisheries, and in order to maintain the population at present levels given the by-catch, immigration from outside

the Barents Sea is required (see Joint Norwegian-Russian environmental status 2008 Report on the Barents Sea Ecosystem. Part I – Short version p.11).

It is perhaps not surprising therefore that we did not see a single seal during our stay.

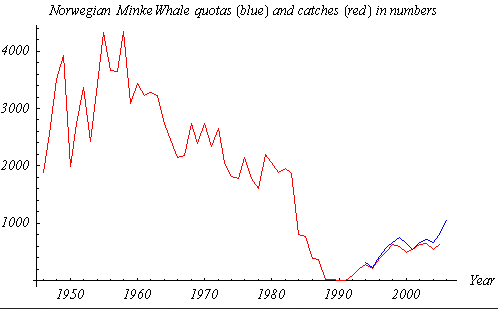

Whaling

Norway restarted commercial whaling in 1993. Coastal Minke whaling had begun in the 1860s and was opposed by coastal fishing communities who believed the Minke brought the fish closer to the shore. An 1880 Whaling Law was brought in to stop whaling too close to the shore and in 1904 the Whaling Protection Law was enacted to stop whaling in coastal areas where fisherfolk were protesting. But commercial whaling was only just getting going and under the aegis of the man behind the exploding harpoon, Svend Foyn, Norwegian whalers searched out new whaling sea areas and countries.

Most whaling in the second half of the 19th century was located either in Svalbard or in the extreme north of Norway near the Russian border.

In June 1903, fishermen destroyed the whaling station of the Tanen Whaling Company in the "Menhaven Riots". As a consequence all whaling in Norway's three northernmost counties was banned for a period of 10 years. Norwegian whalers moved their operations further afield to Iceland, the Faeroes, Shetland, Newfoundland and Chile (see Wikipedia: Whaling in Norway).

Martinsen argues that the government and whaling/fishing lobby in the 1990s set out to re-educate the Norwegian public about the 'scientific facts' of whaling, casting the Minke whale in the role of 'pest'. This was helped by the strong linkages between the industry and Ministry of Trade, Industry and Fishing.

Quite why Norway was willing to risk its international reputation on an industry that was commercially insignificant is unclear. Perhaps an assertion of independence or difference. Or in order to protect much more important fish stocks for human exploitation?

In the 1980s and 90s Minke whales were vilified for 'eating our fish' and being 'the rats of the sea' with a small brain and not being suited to whale watching. In 2004 this position had changed with a government view that stable Minke stocks would not have a significantly deleterious impact on fish stocks.

A 2009 Ministry of Fisheries and Coastal Affairs White Paper on sea mammals seemed to go back to the earlier view that sealing and whaling industries needed to be expanded while strategies were put in place to counter international opposition.

Since 2006 Norwegian whale quotas have stood at 1,052 Minke whales.

Above from Martinsen, S., (2011) 'Whales in Norway', in Brakes, P. and Simmonds, M.P., (ed.s) Whales and Dolphins: Cognition, Culture, Conservation and Human Perceptions, Routledge, pp77-88.