Historical Sites VI: Asinou (Panaya Forviotissa)

Asinou is the local name for the church. It's more formal 'Panaya Forviotissa' means either 'Our Lady of the Pastures' or 'Our Lady of the Milkwort'.

Dating from the beginning of the twelfth century the church is set in a splendid isolated setting. Perched high on a spur of the deeply cut Asinou valley it is surrounded by birdsong floating up from the almond trees and rush thickets of the valley bottom.

The hills climb quickly from the narrow cultivable land and soon Brutia Pine take over as the hills go back and back into the high Troodos that sweep down from the heights.

On my first visit on a cold January day with snow melting in the church yard I was the only person around. The church was locked but I didn't really care. The building, the setting and the solitude were enough. Not that I was quite alone. Someone in the taverna opposite the church had a leaf-blower going.

Any guide book will tell you about the church. I was struck by its diminutive size, rusticity and steeply-sloping stone-tiled roof. If it didn't look like it had grown out of the landscape - the rectangular raised base knocked that particular fantasy on the head - its certainly looked a piece with it.

A snow-man with grass hair and a checked-scarf stood at the edge of the little walled enclosure peering down the valley, as if expecting visitors. The birds continued to sing below. The leaf-blower continued its whining.

On a second visit I got to go into the church. The only other visitor was a rather gaunt, shaven-headed, willowy man with a camera and pointy shoes. He exuded a belligerent intensity as he engaged the custodian in conversation. I felt ridiculously exposed for some reason - was the intensity some kind of pious religious repellent?

The inside of the church lacks the usual over-the-top ornamentation. Indeed it is simplicity itself but for being absolutely smothered with frescos from the bottom of the walls to tops of the ceilings. I was not blown away by them. There just seemed to be too much going on. It is a really in-your-face experience. Too much iconography. There was nowhere to escape to, to get a sense of perspective. Everything clamoured for attention. Nothing got it. And I felt an obligation to be impressed that wasn't happening for me. Plus photography was prohibited. And that spooky guy was spooking me.

The inside of the church is a kind of immersive experience, an installation or piece of video work presented as still images. This time it just didn't grab me.

Later I thought that maybe I just didn't have the interpretive tools with which I might have made sense of the wall paintings (it turns out they are not technically 'frescoes' because they were not painted into wet plaster).

Or that I just felt antagonistic to the contemporary Orthodox Church (which I do). Or that I was unreflectively castigating all things Byzantine, Eastern and external to the ur-narrative that links the 'Classical World' to the 'Renaissance World' to the 'Enlightenment' and beyond (that's 'me').

Spending a few days looking at Edinburgh's Enlightenment pretensions to be the 'Athens of the North' and the 'Rome of the Forth' helped. So I've spent some time trying to inform myself about Byzantium and the wall paintings. See here my Byzantium and Cyprus and Byzantium pages and what follows below.

To get an initial idea of what one of the Troodos painted churches is like I would suggest clicking on the links below which give a fantastic sense of what it is like to be in the Asinou church on a bright sunny day with all the doors thrown open.

Click

here for a virtual tour of the 11th century nave of the church.

And here for the late 11th century narthex redecorated in 1333.

And here for outside. But make sure to come back, hey.

Panagia Forbiotissa (the spelling is always changing) used to be the katholicon (monastery church) of the Monastery of Forbion, as its name implies. According to the dedicatory inscription above its south entrance, which is dated to 1105/6, the church was built with the donation of Magistros Nikephoros Ischyrios, who subsequently became a monk with the name, 'Nikolaos'. The monastery was founded in 1099 and it functioned until the end of the 18th century, when it was abandoned. Today no traces of the rest of the monastic buildings survive (see Department of Antiquities).

The twelfth-century church of Asinou consisted of a single nave with rounded apse and three blind arches on the north and south walls, divided by pilasters carrying transverse ribs which supported a waggon vault. The narthex with rounded apsides and cupola was added later in the mid-twelfth century – and redecorated in 1333 (see D. C. Winfield and E. J. W. Hawkins (1967) ‘The Church of Our Lady at Asinou, Cyprus. A Report on the Seasons of 1965 and 1966’, Dumbarton Oaks Papers, Vol. 21, p.261).

I find the very language of church architecture alienating - I have blindly staggered around the word 'narthex' without really knowing what it means. It turns out it does not have a precise meaning.

Wikipedia Narthex defines it thus,

The narthex is an architectural element typical of early christian and byzantine basilicas or churches consisting of the entrance or lobby area, located at the end of the nave, at the far end from the church's main altar. Traditionally the narthex was a part of the church building, but was not considered part of the church proper.

The word itself comes through Latin from the Greek word for 'scourge' or 'giant fennel' (and the Giant Fennel is itself not even a member of the Fennel family). But apparently the narthex was the place for penitents and those who were not fully paid-up members of the congregation. It is sometimes referred to as a 'vestibule' when it is part of the body of the church and a 'porch' when not.

The narthex at Asinou is nearly half the size of the original church and in addition has two apsides (singular apsis) which gave the church the form of a truncated cross. The narthex is separated from the nave by a thick wall and small doorway. In Eastern Christianity some penitential services are held in the narthex rather than the nave. In the Russian Orthodox church funerals are held in the narthex.

The narthex is at the west end of the nave because the altar was placed at the east end from where Christ was believed to have come.

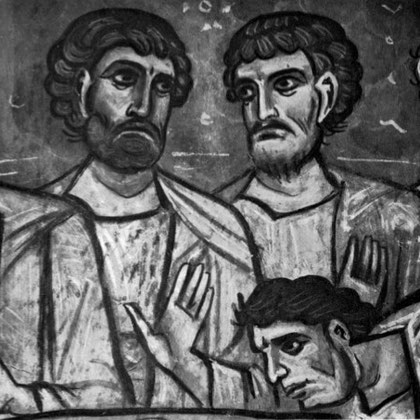

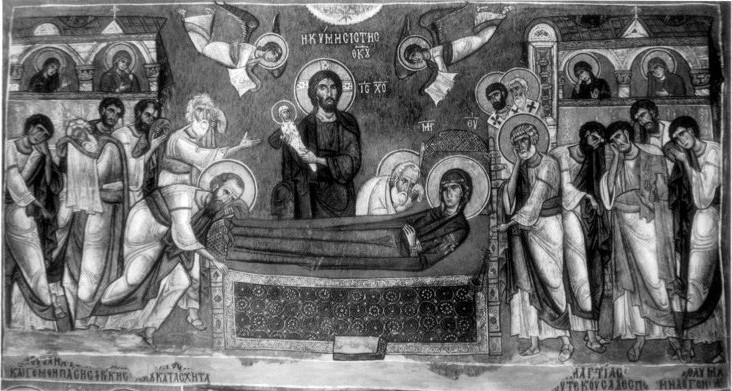

Black and white details of the west wall lunette

The original decoration comprised a cycle of the Twelve Feasts, together with additional scenes in the vaults over the east and west bays and on the north wall of the center bay (Winfield and Hawkins above p.262).

The Dumbarton Oaks cleaning programme started in 1965 (with collaboration of the Department of Antiquities and the Bishop of Kyrenia in which diocese the church lies). The cleaning was carried out with a mixture of ammonia, alcohol, acetone, liquid soap, and water. The 12th Century paintings (1106) were in very blackened condition whilst 14th century ones were relatively free from dirt suggesting church was well used in 12th and 13th centuries ‘but little used after its redecoration’ in 14th century (p.264).

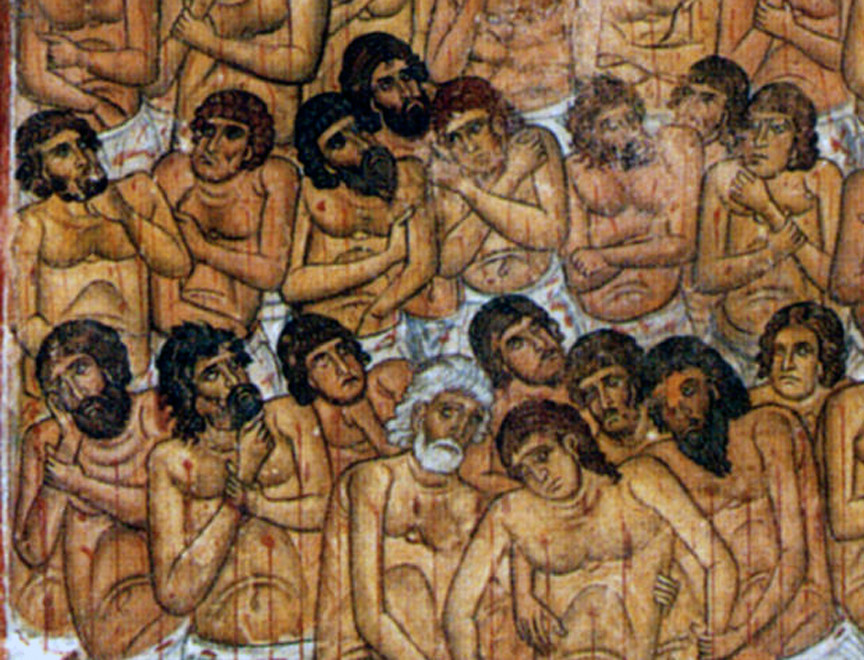

The paintings themselves are painted on 1-2cm layer of plaster with chopped straw and painted in primary colours - red, yellow, green, blue, black, and white. An orange-red and gilt were used sparingly. The paintings were made very quickly and done in one short season, with dash and verve, often using a three-tone palette to suggest shadows and highlights. The exception was the faces of the figures where a more sophisticated palette of mixed tones and colours was applied using fine brushwork.

D. C. Winfield and E. J. W. Hawkins (1967) ‘The Church of Our Lady at Asinou, Cyprus. A Report on the Seasons of 1965 and 1966’, Dumbarton Oaks Papers, Vol. 21

For my money the paintings of the western end of the nave are the greatest in the church. They have character, movement and individualism. They feels and express emotion and interest in the world around them. In the eastern end of the nave the figures and painting style seem more mannered and formulaic with lots of white outlines. I didn't see in the apse unfortunately.

The narthex that was redecorated in 1333 seems to me more mannered still with a static frontality that renders the figures little more than symbols and cyphers. The colours are brilliant but there is a sense of being hemmed-in by figures of an almost benign and indifferent judgement secure in their own righteousness.

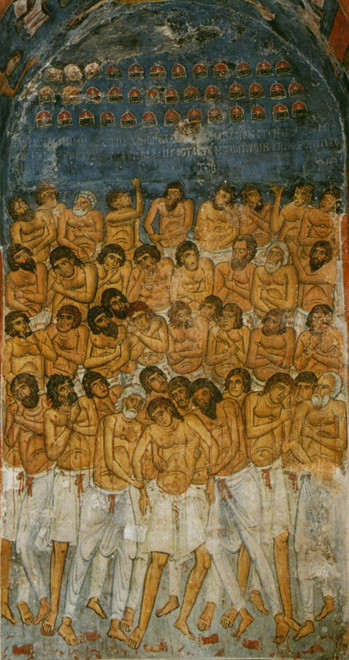

Marc Rubin in the Rough Guide says that the fresco style is 'highly sophisticated and vivid' (2009: 228). Certainly the 40 Martyrs below manages to convey a quiet sense of individualism and the figures are painted with great fluidity.

I had a walk up the forest trail as light rain fell. The forest road was very muddy. A pick-up passed me with cut-wood thrown in the back, The cold weather was getting to people. The driver slowed and asked me who I was - his mother looking frail and cold beside him. 'Just a tourist?', he checked and relaxed and drove on.

I was amazed to see a field of barley already in ear, in early January. The first almond blossom was out. Field calendulas and wild rocket were in flower as were Romulea phoenicia. Hawthorn flower-buds stood erect in the rain. Flocks of chaffinches moved between the almond trees keeping a respectable distance from me.

Peace reigned and rain rained.