V. The Milford Road: a photographic journey.

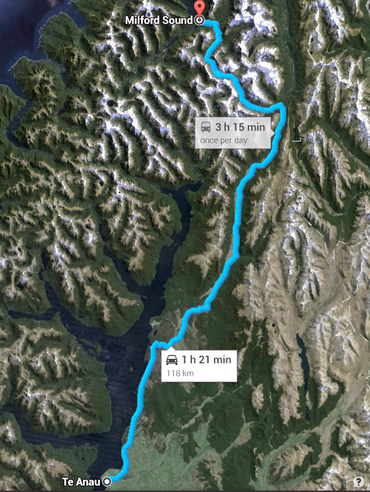

The Route

Notwithstanding the pressures on the Milford Road and its importance as a tourist artery in the economic body of New Zealand it is one of the most exciting roads I have ever driven along.

Over its 119km/74 mile course it goes from the placid waters of Te Anau through increasingly wild and rugged country until it enters the deeply glaciated valleys on the other side of Lake Fergus. (Lake Fergus was named in 1889 after Thomas Fergus, the MP for the Wakatipu district.)

From here it is like taking a tour through a geological battefield - huge rock walls rear up from the valley floor, terrifying rockfalls hundreds of metres wide are scraped back from the road edge and rivers roar through the valley floors.

Just as it seems it cannot get better the road jacks up to the Homer Tunnel - here a vast wall of rock 512 metres (1,679ft) high blocks forward progress. Pass through this wet, dripping dimly lit unlined cave through blasted rock and you emerge on what seems a precipice with a vertiginous descent down the cwm wall to the valley floor. Everywhere there is water running, oozing, seeping and falling helpless into space.

And then through narrow defiles and more blood-curdling valleys you arrive at Milford Sound.

The road is indeed 'a unique journey into the heart of Fiordland National Park' (FNPMP: 2007). In fact, it is the only road into the heart of the otherwise inaccessible park. And having been mesmerised by the grandeur and tumbling verticality of it all you have to turn around and do it all again in reverse order, all the way to Te Anau.

The road hugs the shoreline of Lake Te Anau for about 29 km until it enters the flat bottomed Eglinton Valley and runs upriver for 33 km passing the hilariously named Knobs Flat.

After Cascade Creek the road runs through red beech forest on the shore of Lake Gunn and Lake Fergus. The road climbs to a dramatic saddle at the headwater of the Eglinton River and pitches down into much deeper and heavily glaciated Hollyford Valley.

Once on the narrow valley floor the road goes upstream alongside the Hollyford River reaching an altitude of 945m at the Homer Tunnel (New Zealand's third highest road).

The road passes through the 1,270 metres tunnel and emerges at the base of a massive 800m vertical rock wall at the head of the Cleddau Valley. A steep descent brings it to the valley floor and the road runs parallel to the Cleddau River for 16 km to Milford Sound.

Photographing the Milford Experience

The photos on this page chart the journey from Te Anau Downs to Milford Sound. There are two sets of intermixed shots - those I took on the journey in - in the early afternoon of a pretty dull high pressure day and those I took on the way out in the early morning of a late summer day.

Taking photographs of the huge mountain walls and dark, shadowed cliffs presents the photographer with all sorts of the problem. Even on a dull afternoon the sky is ridiculously bright in comparison with the mountains standing against it.

This means making compromises - burning-out the sky to get somewhere near the natural colour and tone of the mountains, or casting them into further darkness in order to maintain the integrity of the sky and the cloud formations swirling about the peaks. A third option is to lighten the mid tones in the photo but this risks bleeding the richness out of all colour and losing contrast.

I've utilised all three techniques and anything else I can think of to bring the photos to life. My overall object is to give a sense of the changing scene and feel as you move down the Milford Road.

I dare say most people, particularly international visitors, only make this journey once in a lifetime and for most that is within the confines, scheduled stops and timetable of a long coach ride

from distant Queenstown. I hope this photographic journey is a bit more enduring.

You could spend a lifetime tramping the paths between Te Anau and Milford in an attempt to capture its moods, intricacy, intimacy, savagery and grandeur. I had four hours and a patient partner, the pressure of getting to our boat on time and the prospect of what turned out to be a hugely long day after the drive out.

I had one amazing coincidence. I took a photo of the contemporary Homer Hut near the entrance to the Homer Tunnel. Four months later I came across a photo of the 1920s Homer Hut by Algernon Gifford that has almost the exact same composition as mine. It is amazing how little the scene has changed in 90-100 years. (They are next to each other further into this page.)

Some notes on the Fiordland National Park

This next section is a series of notes and quotes (the latter pulled out of the 2007 Fiordland National Park Management Plan) on the Fiordland National Park..

I've found these national park management plans really useful as they give concise descriptions of the geology, flora and fauna of the national parks and the that issues that confront each of them.

A biogeographic island

'Fiordland is almost a biogeographic island with its eastern boundary of major lakes and rivers stretching - almost unbroken - from Martins Bay in the north to Te Waewae Bay in the south. Collectively, these lakes and rivers comprise the largest system of inland waterways in New Zealand. The three main lakes, Hauroko, Manapöuri and Te Anau, are also the deepest in the country (462 metres, 444 metres and 400 metres respectively).'

Fiordland National Park Management Plan 2007 p.17

Gondwanaland preserved

Te Wähipounamu - South West New Zealand - is considered to be the best modern example of the primitive taxa of Gondwanaland seen in modern ecosystems – and .is of global significance. The progressive break-up of Gondwanaland is considered one of the most important events in the earth’s evolutionary history.

'New Zealand’s separation before the appearance of marsupials and other mammals, and its long isolation since ... [enabled] the survival of the ancient Gondwanan biota ... to a greater degree than elsewhere. The living representatives of this ancient biota include flightless kiwis, carnivorous land snails, 14 species of podocarp and ... beech ...'

The region contains outstanding examples of plant succession after glaciation, with sequences along altitudinal (sea level to permanent snowline), latitudinal (wet west to the dry east), and chronological gradients (fresh post-glacial surfaces to old Pleistocene moraines).

From the UNESCO entry for Te Wähipounamu - South West New Zealand as a World Heritage Site.

An uninhabited land

The Fiordland National Park, (established 1952) is New Zealand's biggest national park (and one of the world's largest temperate national parks). It has an area of 12,500 km² (1.2m hectares).

Compare this to the USA's Yellowstone 8,983.2 km2 and South Africa's Kruger National Park 19,485 km².

Fiordland National Park forms a major part of the Te Wahipounamu World Heritage area (1990). Nearby Mount Aspiring, Mount Cook, and Westland national parks form the other parts.

There is no terrestrial farming of any kind in the park and very little permanent habitation by humans. In this it is quite remarkable.

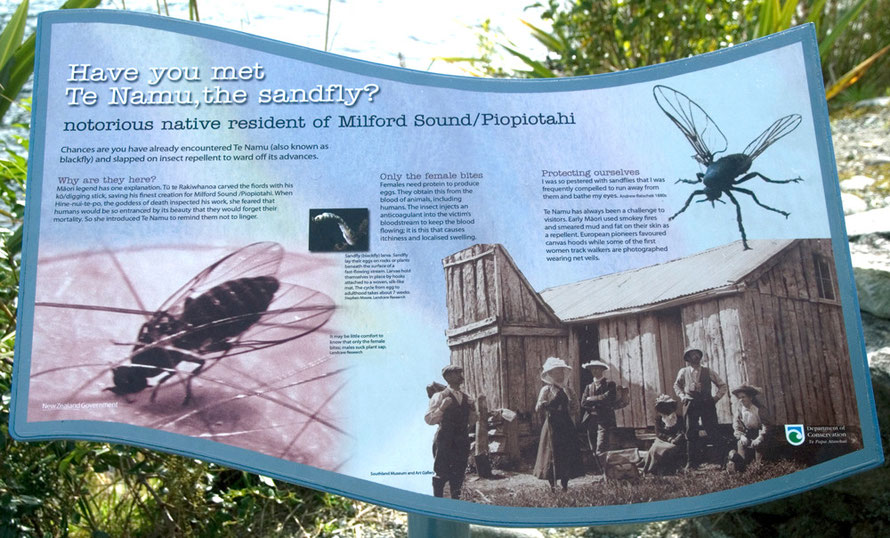

The absence of flat, fertile land, the massive annual rainfall, the plague-like proportions of the sandfly and the physical isolation do not make it a desirable place to live.

Yet in many parts of the world even the most marginal land has been inhabited by people and a living (of sorts - brutal and short but a living nonetheless) wrung from it. And the lakes, fiords and seas off Fiordland are relatively rich in edible sea life.

Being such a young part of the world in terms of its human presence - a maximum of one thousand years - and being so far from the main centres of population of the world the marginal lands of New Zealand's west coast and Fiordland never came under the intense pressure to be 'settled' (or used as a dumping ground for surplus populations - as in the Highland clearances) as happened in other parts of the world.

Human occupation of the European Alps has a long history,and impacts have been slow but intensive; virtually no valley today is without road access. In the Southern Alps, impacts have been comparatively recent and very scattered, especially on the very wet western part of the main divide.

(From Jeanneret, F. (2001) Different Human Impacts in Similar Settings: Old and New World Alpine Landscapes in Comparison, Mountain Research and Development, Vol. 21, No. 4, p.319.)

Coastal Environments

'The long Fiordland coastline has a great variety of coastal environments. The steep- sided fiords support marine species unique in the world. Species composition is largely influenced by the patterns of water circulation that develop in the fiords. After heavy rain in Fiordland, a dark brackish layer of fresh water (from river inflows) floats over the seawater. This layer filters the sunlight and creates very dark but clean marine habitats at quite shallow depths. It is for this reason that black coral can be found at shallow depths.'

Fiordland National Park Management Plan 2007 p. 18.

Soils

In general the soils of Fiordland are naturally low to very low in fertility and biological activity, and weak in structure. They are liable to periodic debris avalanches (normal geological erosion), scree, sheet and gully erosion.

Fiordland National Park Management Plan 2007 p.44

On the steep slopes of [the upland plutonic] terrain the soil cover is usually thin and commonly consists of several inches of forest litter or peat, with a very shallow sandy layer at the base and ... chemical decay appears to be slow in the cool, moist climate of Fiordland

Wood, BL (1961) Geological Factors in Fiordland Ecology, GNS.

Rare and endangered

The deep valleys of Fiordland are one of the last refuges of New Zealand's takahe (Notornis mantelli) - a goose-sized rail that was considered extinct for 50 years

until deer hunters found a pair in the Murchison Mountains in 1948. There is now a large takahe reserve within the park.

The less fortunate kakapo (Strigops habroptilus), the world’s heaviest (and flightless) parrot, has been pretty

much eradicated from the mainland areas of the park by introduced predators - particularly the stoat. It now only survives on island sanctuaries where predators have been trapped, poisoned and

sniffed out.

The broader area of South West New Zealand is also home to the entire population of the South Island subspecies of brown kiwi (Apteryx australis), New Zealands rarest Kiwi, the rowi (Apteryx rowi), the only significant remaining populations of the seriously declining mohua/yellowhead (Mohoua ochrocephala), the only large populations remaining of kaka and kakariki/yellow-crowned parakeet, and the only remaining population of pateke/Fiordland brown teal in the South Island.

See the UNESCO entry for Te Wähipounamu - South West New Zealand as a World Heritage Site.

Flora and fauna threats

There is no longer any stock grazing in Fiordland National Park with the final phasing out of sheep grazing in the Eglinton Valley in 1998. p.53.

Rising deer numbers are a serious threat to Fiordland National Park. And possum are a continued menace and in some areas Canada Geese have become established. pp52-3.

Some of the key weed threats in Fiordland as identified in the Southland Regional Pest Management Strategy (2002) include barberry, boxthorn, cotoneaster, German ivy, lagarosiphon, nodding thistle, old man’s beard, ragwort and spartina. Californian and Scotch thistles are also considered a problem', Fiordland National Park Management Plan 2007 p.52-3

The Three Great Walks

Fiordland is the location of three world-class multi-day treks: the Milford Track, Kepler Track and the Routeburn Track.

These are well organised with high quality huts, guided walk operations and booking systems. The three walks 'absorb the bulk of the backcountry users in Fiordland'.

The number of walkers (or 'trampers' as they are known in New Zealand) on these paths is limited. In 2007 the number was 14,000 for the 54km Milford Track while daily overnight entrants are limited to 90 - of which 40 are for independent walkers This due to limited hut capacity FLNPMP p.145-6.

Impressions

Waiting at the lights at the eastern portal of the Homer Tunnel - a red sign tells us that there are four minutes and 12 seconds to wait before we can proceed. The tunnel entrance is a lip into a

dark mouth.

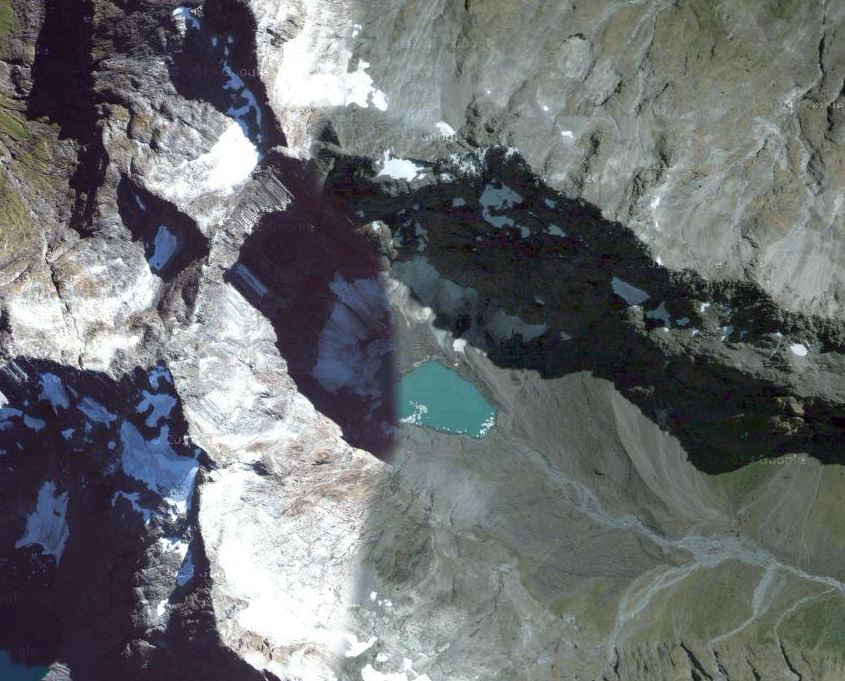

We get out of the car overawed by the scene above us. To the north the McPherson Falls tumble 160 metres from the cirque above. The landscape is elemental. Bare walls of rock dominate and below them vast scree slopes. Plant cover is minimal at this altitude (940m).

Its cold and there is a sense of impending danger. Little did we know of the tunnel workers and road supervisors killed by avalanches at this very spot.

Above us tower Mts McPherson (1,931m), Talbot (2,105m) and Crosscut (2,263m), their permanent snow fields dazzling in the swirling clouds. Water glistens on the bare rocks, tumbling down to the valley floor of lichen-red boulders in the Hollyford river stream bed.

The tunnel timer ticks down and we scramble back in the car. The tunnel is dimly lit and descending at a gradient of 1:10. Water drips from the ceiling. Its snow melt that has worked its way down from the arete 500m on top of us.

The tunnel opens out into what seems like a wide cavity with no walls. It feels like we are in free fall in the darkness, the lights from the car behind bouncing around the cockpit.

The 1,270 metres pass and luckily we don't know about the coach fires that have taken place inside it. Nor the Great Nude Run that charges through each year.

We emerge into a cauldron of rock from under a temporary rockfall portal. The road snakes steeply through a vast jumble of moraine and debris.

Returning the next day we wait longer at the western portal. Two kea are standing by the roadside pecking at the luminescent wrappings on the road works barriers. We are up in the cloud and it is wet.

I run over to the birds and take pictures. They seem oblivious to my presence.

Above us the rock wall climbs into the clouds. Everywhere water is running down it through beds of moss. In places the rocks are blanched a grey-white from rock-flour left by recent rock falls.

It was above here on the dizzying cliffs that engineers drilled and blasted out a 2,000 tonne pinnacle of rock that had only a 20 per cent attachment to the rock wall. Special care was taken to fragment the rock with a high explosive charge to stop massive boulders smashing on to the road below.

We clamber back into the car and leave the dripping cauldron of the western portal behind as we enter into the darkness.

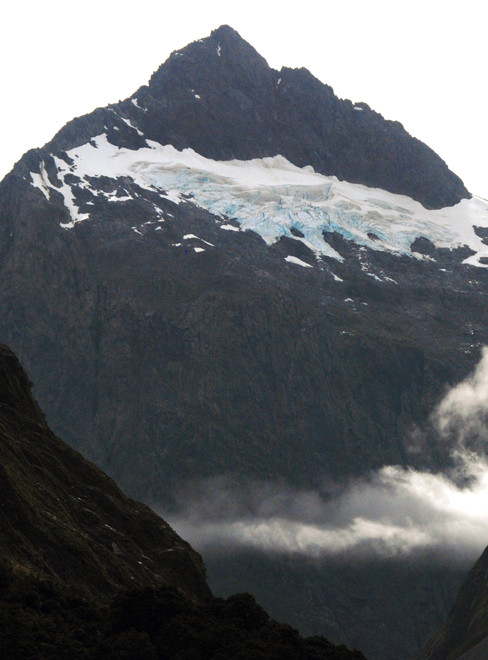

This time the light is brighter as we emerge from the tunnel. The long valley races downhill before us, the imposing bulk of Mt Christina rearing up to 2,474 metres above us.

Standing on the historic suspension bridge (built 1940) over the Tutoko River.

The mountains tower over us but I had so wanted to stop here. I walk out on the weathered ash-grey planking of the bridge.

The river rushes beneath us making its way between huge pale granite boulders. The water is ice-blue. It really does look like a Fox's Glacier Mint. Beech forest crowds its banks and leans out over the streambed.

Further up the valley below the swirling clouds that obscures Mt Tutoko (2,723m) from view the massive bulk of the Darran Mountains tumbles upwards, dark and implacable.

A sign tells me that Tutoko-Topuni is a 'taonga' (a treasure) of the Ngai Tahu iwi (see my pages here for their history). Tutoko was a chieftain and the topuni was his cloak. In current usage 'topuni' is a way of acknowledging the cultural significance of a particular place or landform and this has been enshrined in the Ngai Tahu Claims Settlement Act of 1998.

I have to tear myself away.

Later I learn that New Zealand has more bridges, per capita than any other country in the world due to its climate and topography.

Arriving at Milford Sound is a relief because we have made it and are on time for our boat. My visions of a lonely quayside could not be more wrong. We stop in a landscaped car park full of cars and campers with people like us getting their gear together for the overnight fiord cruise.

The sun shines and we walk along a shaded walkway between towering beeches, our suitcase wheels merrily pip-popping over the planking.

The Sound comes into view magnificent and imposing. We work our way into the big cavernous reception centre and check out our tickets. The last day trip boat docks and a loud group of Americans makes their way to the waiting coach.

Barren Peak towers above us. Outside the sandflies are thick and biting like mad.