Cyprus: Social welfare fallout from the bailout

Most recent additions at bottom of page

Social Protection

Cyprus about 18% of GDP (2006) on social protection compared to an EU average of 27%. It is the ninth lowest spender on social protection in the EU 27 by percentage of GDP.

- Cyprus spent 4.6 per cent on sickness/healthcare in 2006 compared to the EU 27 average of 7.5 per cent.

- Cyprus spent 6.8 per cent on pensions in 2006 compared to the EU 27 average of 11.9 per cent.

- Cyprus spent 0.0 per cent on care for the elderly in 2006 compared to the EU 27 average of 0.5 per cent (the lowest in the EU along with Bulgaria and Romania).

Combating poverty and social exclusion A statistical portrait of the European Union 2010 (Eurostat) p.96-98

Not surprisingly given these low levels of social protection as measured by percentage of GDP the impact of social transfers on the reduction of that percentage of the population at-risk-of-poverty is low in Cyprus. In 2007 social transfer lowered the at-risk-of-poverty percentage of the population from 22 per cent to 16 per cent - a fall of 6 per cent - whereas the EU average was 26 per cent to 17 per cent - a fall of 9 per cent (all percentages approximate).

Looked at another the percentage reduction in the at-risk-of-poverty after social transfers for the total population was 24 per cent in Cyrpus compared to an EU 27 average of 35 per cent. Cyprus scored the EU average for reducing poverty risk for children under 18 and was the worst offender in the EU 27 with regard to the impact of osicla transfers in reducing poverty risk in the over 65s both relatively and absolutely.

Not surprisingly social protection receipts - the money paid into social protection by employers, employees and government are low in Cyprus - about 21 per cent of GDP compared to the EU 27 average of 27 per cent.

Combating poverty and social exclusion A statistical portrait of the European Union 2010 (Eurostat) p.101-2.

Material Deprivation

Eurostat provides a vast array statistics to measure social exclusion and material deprivation (see main web site here).

The table below shows one of these indicies - severe material deprivation - and ranks Cyprus against other EU members in 2011. From these I would suggest that Cyprus has a medium to high rate of material deprivation in comparison with other EU countries in that nearly 11 per cent of the population has an equivalised disposable income below the risk-of-poverty threshold set as 60% of the national median income.

Severe material deprivation rate by NUTS 2 regions

% of total population 2011

(The persons with an equivalised disposable income below the risk-of-poverty threshold, which is set at 60 % of the national median equivalised disposable income.)

Norway 2.3

Spain 3.9

UK 5.1

Sardinia 9.4

Cyprus 10.8

Poland 13

Greece 15.2

Sicily 25.3

By another measure of material deprivation as economic or durable strain (the ability to buy certain items) Cyprus is ranked sixth worst where over 30% of the population suffer material deprivation. Combating poverty and social exclusion A statistical portrait of the European Union 2010 (Eurostat) p.55

The next table shows the percentage of the population at risk of poverty or social exclusion, which is a broader measure of social disadvantage. Cyprus has a medium relative ot the EU rate of people at risk of social exclusion and poverty.

People at risk of poverty or social exclusion % 2011

(Persons who are at risk of poverty or severely materially deprived or living in households with very low work intensity.)

Norway 14.6

UK 22.7

Cyprus 23.7

Spain 27

Poland 27.2

Greece 31

Sardinia 32.2

Sicily 54.6

Inequality

Cyprus scores about average in the EU in terms of levels of inequality as measured by the Gini coeffient but what is striking is that its 2007 tax and cash benefits regime had the least impact on reducing the Gini co-efficient of all EU members.

Denmark is greatest with a 15% reduction in Gini coefficient. Cyprus is least with 4%.

On the face of it, and this requires further clarification, the tax and benefits systems in Cyprus appear to be poor at redistributing income through transfer payments. Other things being equal, in times of crisis state programmes and taxes are likely to be relatively ineffective at sharing and ameliorating the impacts of the crisis.

(See Eurostat Income and living conditions in Europe 2010 Edited by A. Atkinson and E. Marlier p.355)

From what little I know about the social organisation of Cyprus the family and the extended family in particular have traditionally been an important mechanism for the redistribution of income and the support of the disadvantaged. Although of course families as much as individuals can be disadvantaged.

How much the family still performs this role given the massive shift from village to urban life and the dislocation resulting from partition of the island is something that would be worth investigating further.

The other organisations that are particularly important in the succour of the poor have been the church, charities and non-governmental organisations.

Groups at risk

The NATIONAL STRATEGY REPORTS ON SOCIAL PROTECTION AND SOCIAL INCLUSION 2008 - 2010, Ministry of Labour and Social Insurance, 2008 p. 16 identified the following groups at risk of social exclusion and poverty

• The elderly 65 years and over with the highest poverty risk,

• Persons who live in one person households,

• Recipients of public assistance,

• Single-parent families,

• Unemployed young persons,

• Unemployed women as well as the inactive female force

• Young persons who leave school early,

• Persons with disabilities

• Economic immigrants and refugees, especially those from third countries.

Groups at risk: the elderly

A recent study of the elderly concluded that

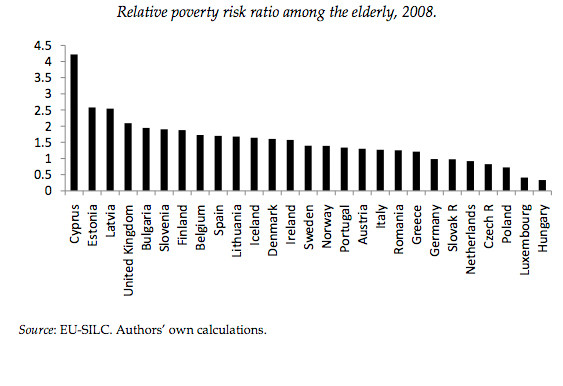

the elderly face [a] four times higher risk of poverty than the working-age population [in Cyprus], when the EU average is considerably lower. This is mostly due to a large wedge between income from wages and income from pensions.

In 2007 Cyprus was ranked first for poverty amongst the elderly in the EU. Estonia, Latvia UK and Bulgaria were also very highly ranked (see Combating poverty and social exclusion A statistical portrait of the European Union 2010 (Eurostat) p.52.

In Cyprus alomst 50 per cent of elderly people (one in two) is in or at risk of poverty.

Koutsampelas notes,

It is also noteworthy that Cyprus has [a] peculiarly larger share of elderly among the poor than other Mediterranean countries (Italy, Greece, Spain and Portugal) despite the fact that it shares similar social structures and welfare state arrangements with them (pp.73-4)

This results from 'pensions income inadequacy.'

Koutsampelas, C. (2012) Aspects of Elderly Poverty in Cyprus, Cyprus Economic Policy Review,6:1.

Elderly poverty has a pronounced gender dimension in Cyprus.

On average women in the EU are 7.3 percentage points more probable to experience poverty than males. In Cyprus the corresponding figure is 10.6 per cent, considerably above the EU average. The largest gender difference is observed for Estonia (21.2%) and Lithuania (19.1%); while the lowest for Greece and UK, where gender differences in elderly poverty happen to be negligible (ibid p.76).

This is largely due to greater longevity amongst women and the inadequacy of widows' pensions.

Ironically Koutsampelas predicts that crisis has a positive impact on the realtive poverty of the poor but only because of increasing poverty amongst the working aged.

In terms of policy Koutsampelas argues that the state is already incredibly limited in what it can vis-a-vis raising pensions. Instead he argbues that carefully targetted redistribution between well-off and poor pensioners needs to be examined along with reforms to the health care and social care systems.

Targeted income transfers (whose financial burden can be expected to be reasonably low) can eradicate pockets of severe deprivation among groups of elderly very vulnerable to poverty and social exclusion (ibid:86).

Progress in Social Protection

In a 2009 assessment of pensions, health and long-term care Petmesidou wrote that there were strong concerns being expressed in public debate about the effects of the crisis on social wellbeing among the rising number of long-term unemployed and, particularly, among low-income pensioners (and other social assistance recipients) for whom poverty rates have been persistently high.

With regard to pensions she wrote that despite a pension reform bill in 2009 that improved public sector pensions (but did not address inequalities between public and private pensions, to the detriment of the latter)‘adequacy of pensions remain a key challenge.’

In the 2012 report she noted that the pensions reforms were still being implemented and that,

Other parameters of public sector pension schemes, such as pensionable age, the formula of pension calculation and the non-taxable lump sum bonus provided at retirement have been issues of confrontations in public debate between the government, opposition parties and the public sector trade unions, but so far they have not entered the reform agenda.

In the 2012 report she wrote, 'No significant progress has been recorded in the reform path towards launching a comprehensive national health system.'

In a u-turn move, the recent announcement by the Ministry of Health that the launching of the GHS should start from tertiary (specialised) and hospital services, so as to shore up the ailing private sector that owns a large part of specialised health infrastructure, highly weakens the initial reform goal of introducing a universal health care system based upon unified primary care. Meanwhile the crisis conditions greatly increased strain on an already overstretched public health care system characterised by considerable inequalities in terms of access to and utilisation of services.

With regard to long-term care decentralisation of services will improve access but the social welfare services are ‘understaffed and the carer/client ratio has deteriorated'. Key challenges remain concerning assessment of future needs and resource requirements, the targeting of provision and coordination between public, private and voluntary providers.

In the 2012 report she noted there was little or no progress in this area:

Finally, long-term care remains fragmented and rudimentary in funding and delivery. Significant reforms that need to be introduced in light of impending demographic change do not figure in public debate.

(see Maria Petmesidou 2009 and 2012, Annual National Reports on Pensions, Health and Long-term Care: Cyprus, European Commission DG Employment, Social Affairs and Equal Opportunities p.1)

Pensions

In 2011 the public pension schme was heading for a bust with payments outstripping contributions.

The average effective retirement age is in Cyprus in 2011was about 63.6 years as pensions can be taken with no penalty from age 63 for both men and women.

Reforming 'pension schemes for public employees is key to reduce growing public pension costs and address long term fiscal challenges.' p.25. (IMF Cyprus Slected Issues 2011).

Mental health and crisis in Greece

A useful article in the FT 27 December 2012 Chaffin on the mental health aspects of the Greek crisis that emphasises the long-term mental health costs of prolonged crisis and a widespread and pervasive sense of uncertainty.

Also notes the corrosive impact of the 'Greek neurosis:'

Andrew Armatas, an Athens psychologist, believes the crisis has played on a typical Greek neurosis: an ever-present fear – communicated by overbearing elders who suffered Nazi occupation, civil war and famine – that disaster is just around the corner.

I would only add that the traumatic effects of the de facto partition of Cyprus and the accompanying displacement and dislocation were widespread and clearly, from studies done on reconciliation, still very much part of the national psyche.

To: Beyond the Cyprus/Germany Standoff