III. Bluff: Gateway to Stewart Island

Bluff is a pretty quiet place with a population of less than two thousand. But on the Saturday afternoon we arrived it seemed even quieter than usual. The sky was overcast and there was a real feeling of having reached the end of the line. There was simply no further south to go without getting on a boat and crossing the fearful Foveaux Strait.

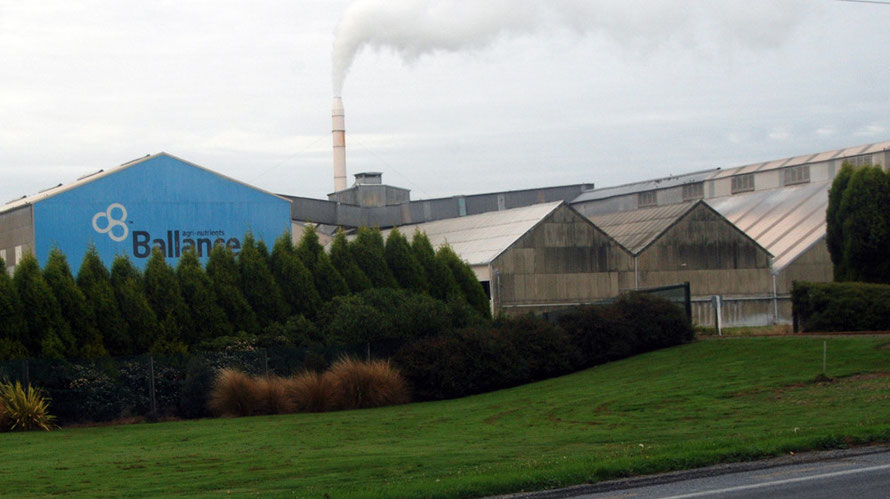

The road into Bluff crosses a wide marshy neck - the Awarua Plains - punctuated only by a Ballance Agri-Nutrients fertilizer plant, a new dried-milk factory under construction and the distant chimney of the Tiwai aluminium smelter.

The stretch of road just has that feeling of coming to the end of the land. The sky gets bigger the trees smaller, stunted and bent until even they are replaced by blasted shrubs and grasses.

We arrived early for the late afternoon sailing of the Stewart Island catamaran a day ahead of schedule. The unseasonally calm weather was a real incentive to get out to Stewart Island as the guide book fanstasy became a slightly anxious reality.

The entrance to Bluff itself is marked by another large fertiliser plant of less modern construction than the Ballance one up the road. There was a whiff of fishmeal in the air. The large natural harbour then opens up on the right hand side of the road in.

The tide was out and a strange islet surrounded by commercial boats and covered in a red-oxide tin shed caught my eye. It turns out this is Colyers Island and the site of a Maori argilite quarry - a hard stone used to make adze heads.

Motupōhue (Bluff Hill) represents the sternpost of the waka - ocean-going canoe - that in Maori mythology is represented by the shape of South Island. Golden Bay and the northern tips of the South Island is the prow (see my page Golden Bay).

We pushed on into the town past old sheds and warehouses that spoke of a past more glorious than Bluff's present. Indeed, the town's promotional website claims that Bluff is the oldest European settlement in New Zealand (although this is convincingly challenged elsewhere).

It certainly was an important early port being relatively close to Australia, from whence many settlers came after first having made landfall there. It was also more convenient for Suez Cannal-bound shipping. The first settlers arrived in the 1820s and it had been an important whaling station for a while.

The Otago and West Coast gold rushes served to increase commercial shipping traffic until the opening of the Panama Canal and the waning of gold fever. At this point the commercial centre of New Zealand began to shift north and Bluff's strategic importance diminished.

At the same time there was a growing centralisation and specialisation of trades and industry and the growth of Invercargill only 30km (20 miles) to the north.

I was pleased however to see that a train still runs to Bluff, down the Bluff Branch, from the end of the Main South Line at Invercargill.

A train pulling containers obligingly chugged into Bluff as we were leaving three days later and The Principal pulled off an excellent shot of the engine and long line of white and then red Hapag-Lloyd containers.

Beyond the warehouses and engineering workshops there are still some striking buildings from Bluff's Victorian pomp - the old colonial Post Office and the Club Hotel.

And further through the town Marine Parade boasts some classic colonial-style bungalows and houses that look out on the North Channel to the sea.

We drove through the town and out to bar-restaurant at Stirling Point to grab a coffee and inspect the condition of the Foveaux Strait.

Far away we could see the hazy outline of Stewart Island and an impressive sign told us that we were 18,958 km from London and a mere stone's throw from the South Pole at 4,810km.

I did feel a long way from home but the momentum of our road trip and the anxiety generated by the Foveaux Strait's fearsome reputation kept the blues away. As did the sandflies which discouraged too much maundering whilst looking out of the melancholy waters to the 'measureless Southern oceans'.

The sign also mentioned that Stewart Island was 35km distant. The Strait looked extremely placid with little or no swell running: almost a dead calm. A pulse of life in the clear waters kept the bull kelp anchored to Stirling Point swishing and swaying but we breathed easy.

We scoped out the diminutive ferry terminal and took a little drive around the backstreets of the town. Called 'Bluff' because it shelters behind Motopohue or 'The Bluff' (265m) the back streets of the burg rise up behind the harbour to the west and are divided into the 'East End' and the' West End'.

A wide grid of depressing, anomie-inducing and non-descript streets of bungalows ran up the incline towards manuka bush and the 'The Bluff'.

We came across a rugby match on a flat playing field and enough parked cars to suggest the local team was well followed.

The place reminded me strongly of Penzance/Newlyn and towns like Camborne and Redruth in the far west of Cornwall in the UK where I lived and worked for 10 years.

There was that same sense of independence of spirit and careworn pride in the face of a world whose centre of dynamism has long since shifted away.

Although Buff is nowhere near as far south as Penzance is north. That is, Penzance is actually closer to the North Pole than Bluff is the the South Pole although I still find this hard to believe. Transfer Bluff to Europe and it would be on a similar latitude to Bern on the Swiss-German border.

It is hard to get one's head around this fact because when you look at an atlas map of New Zealand there is almost no land - save bits of Chile and Argentina half a world away - to the south. You simply assume it is closer to its pole than say the Shetlands in the Northern Hemisphere because there is nothing between it and its pole. I think.

I've written more about this weird disorienting feeling of hemispheric comparison and confusion here: Southern Exposure.

Further along we came across a grim low-rise block of rendered brick flats surrounded by a corrugated iron fence that would not have looked out of place in an ex-tin-mining town in West Cornwall.

However, although the little town had that slightly woebegone feel of a place at the end of the line and land that has seen better days it did not bear signs of desperate poverty or rampant anti-social behaviour that gets depressingly familiar in West Cornwall.

In fact Southland had the lowest unemployment in New Zealand in 2013 standing at 3.8 per cent in May. A local economist said that despite worries about the future of Bluff's aluminium smelter strong fundamentals and low wage made it easier for firms to hire people in the region, while more dairy conversions were a positive factor.

There was something to do with the quality of the light and that end of the line feeling that kept tugging me back to Newlyn. I used to go and watch the Newlyn- Penzance Pirates rugby team on grey saturday afternoons. 'Come on you Pirates!' we'd shout in cod Cornish accents in the little stand as some bunch of posh boys from Esher in Surrey looked like getting the advantage.

So the rugby and light, the boats in the harbour, the air of hope and decay and the infiltration of the everyday-workingness of the port into the town all seemed very familiar.

Amazingly the pub, the Eagle Hotel, was advertising a 'euchre night' on Sundays at 6pm. I'd never fathomed how to play euchre but it is still played in Penzance clubs and pubs.

It seemed like I was in a world away from home and yet they were so different. That strange paradox of familiarity and difference was in play again.

I dropped The Principal at the little ferry terminal - which had been taken over by a group of disencoached German youth who seemed to need to stretch out on the floor while catching up on a bit of music and/or sleep - and parked the car in the secure car park.

I popped to the local supermarket and mingled with scant saturday afternoon shoppers - the sky greyer and gloomier than before.

I bought pathetically few things for our forthcoming wilderness but it took an age to do it. I no longer remember what particular I was searching for, knowing that it would be somewhere, but I went through that confused irritation of unfamiliar aisles and shelves.

The checkout woman was very friendly and was not at all nonplussed when I returned ten minutes later to pick up some other essential for our Stewart Island bivouac.

It reminded me of the time I returned to a Marks and Sparks in the City of London to get a chicken. At the checkout - the same one I'd just used - I said to the woman serving - 'Would you believe, I forgot to get a chicken?' She replied, impeccably, and with no more and no less, 'Innit'.

With an hour before kick-off I slipped out of the fug of the waiting room and headed up to the harbour wharves to get a few more photos.

A planked bridge led out to what was probably the original harbour. Some of this had been stripped of its boards revealing startlingly clear blue-grey water sucking at the piles beneath the stark, ash grey moss and grass encumbered joists.

At one end of the section of unplanked wharf sat three shag (shags?) busy preening and oiling their feathers. I snappped off a photo thinking not much of it only to realise months later that at least one of these - what I thought at the time were ubiquitous and generic 'shags, innit' - was a Stewart Island Shag.

The Stewart Island shags are large marine shags (as opposed the lovely little South African shag here in Montagu) and are found north to the Waitaki River in the South Island of New Zealand.

Interestingly, the Stewart Islands shags decline in size the further south one goes - the Otago birds out-shagging the Stewart Island ones, if you will.

It seems only right at this juncture that I should haul up my photo of Stewart Island Shags on the Otago peninsula to make the comparison, all other things being equal.

Comparing the two photographs which were taken days apart I would say that the Otago Stewart Island shags look sleeker and plumper than their Bluff cousins and their feet look bigger and pinker.

Confusingly the Stewart Island shags have variable plumage and in effect come in two varieties - the striking black-and-white plumage of the pied morph and dull dark brown plumage of the bronze morph that apparently can become, iridescent 'in the right lighting conditions' (NZBirdsOnline).

The Bluff ones are clearly the bronze version where the Otago two above split the difference - one is pied and the other is the dark brown with the very evident effervescent blue-green sheen coming of its wet plumage.

Estimates of population size vary between 1600-1800 pairs, to fewer than 5000 birds. Threats to the Stewart Island Shag include entaglement in nets and disturbance to nesting colonies.

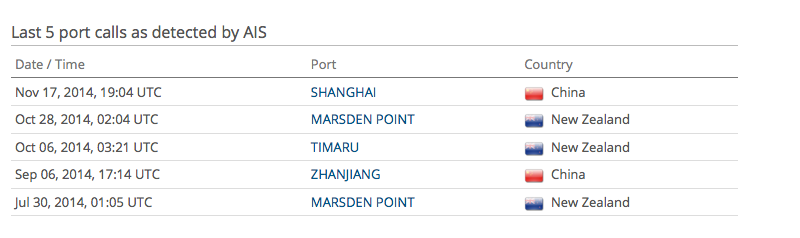

I walked further out past guys fishing and the huge sweep of water of the Bluff Harbour bay running of to a distant and spectacular view of the Southland mountains on the horizon. Further up the harbour on the newer Island Harbour there was a massive bulk carrier moored up and loading logs (presumably for the Chinese market).

This was the 20,000 tonne Kwela out of Panama and owned by a Japanese shipping company. I read in the NZ Herald that the ship had been blown off her anchorage by a fierce gale in Wellington harbour in 2013 where she was also picking up logs.

In front of it was a boat registered 'GOM 379'. This turns out to be a Republic of Korean (KOR) flagged stern trawler fishing vessel of 60 metes length and 700 gross tonnes built in 1974. It is classified in New Zeland as a Limited Processing Vessel allowing it to catch and process fish whole and ‘headed and gutted’ for export.

The ‘GOM 379’ can freeze about 9.5 tonnes of product every 6 hours (about 38 tonnes per day) and can hold up to 450 tonnes of product before it must return to port to discharge (See Submission to the Ministerial Inquiry into the Use and Operation of Foreign Chartered Vessels from Nrothland Deepwater Partnership, 2011, p.4).

For more on the scandal of the use of Foreign Chartered Vessels in New Zealand waters see my page The New Zealand Fishing Industry.

Two 300 tonne white tugs - the Hauroko and the Mangwai - were moored up and a few other coastal craft were in evidence.

The inner habour had a fair smattering of day fishing boats linked to the famous Bluff Oyster fishery and one or two craft offered adventure cruises.

Bluff is also an important starting point for muttonbird/titi gathering forays to the muttonbird islands that lie between Bluff and Stewart Islands (see here my page In Search of Blueys and Sooties and the tragedy that recently befell one of these trips).

There was also a busy looking lobster processing plant belonging to Ngai Tahu Seafood where we saw a bunch of women workers taking a break on our return. For the Ngasi Tahu Waitangi Trubunal settlement and their social investment empire see my pages in the Maori: Travails of the Ngai Tahu section of this website. )

The rest of the town was a bit of a mish mash with train tracks and oepn spaces that had once housed portside industries.

I had got it into my head that Stewart Island was barely inhabited and lacking in but the most rudimentary of food and wine shopping opportunities. In fact it has a well-stocked shop with fresh bread and plenty of choice but just in case we stuffed all our food and wine into a huge suitcase which practically took my arm off going down the walkway and over the boatside of the ferry.

A longish wait ensued until the catamaran ferry pulled into the quayside. Given the ferocity of the Foveaux Strait I had expected something more akin to the sea-going tug that I once took to go from tiny Baltimore on the south west tip of County Kerry in the Iish Republic to Cape Clear Island.

But no, instead, we were going to go on a type of craft that had already alarmed us in post-Cyclone Lusi swell that we had encountered on a trip to Weheke Island near Auckland two weeks earlier.

The crew seemed to faff around for ages before we were allowed to get on - perhaps so we couldn't change our minds and get off. The passengers were few in number and no-one sported a massive bag like mine.

Loaded with my chattels and supplies it all seemed a bit much. On the return journey my bag was embarked compulsorily by the lift arm on the back of the ferry in a small wheeled open bin - ironically when it had been divested of its comestibles and drinkables.

We stowed our gear inside, noted the prominent placing of sea-sick bags and notices advising passengers on how to keep their breakfasts gut-sides in and went out on the deck at the back of the boat.

The captain/driver revved up the engines and we gained way with a huge amount of noise in the North Channel that leads out into the Strait.

We worked our way along the sea-side of Marine Parade past the colonial bungalows and the stark raised basalt obelisk of the Bluff War Memorial (46 fallen from this little town in 1914-18), past the black-and-white harbour light pillbox at Stirling Point and out into the 32km-wide Foveaux Strait.

For a new history of Bluff see this Ngai Tahu page precis of Dr Michael Stevens book, Between Local and Global: A World History of Bluff. Bluff

has a strong Maori presence.

In the 2006 census, 43 per cent of Bluff residents self-identified as Māori, statistically surprising considering only 11.8 per cent of Southlanders and 15 per cent of New Zealanders claim the same connection. It is one of few places in Te Waipounamu where large numbers of Māori families actually live close to one of their marae. Many families maintain a lifestyle that revolves around the seasonal collection of mahika kai, traditional resources like tītī (muttonbirds), tio (oysters), and other inshore fisheries.

Bluff's population peaked at 3,000 in the 1970s, largely due to the Ocean Beach Freezing Works, established on the town’s outskirts in 1891, which led to the port being New Zealand's premier

exporter of frozen mutton and lamb in the 1960s. The plant closed in 1991.

Freezing and latterly chilling plants are an important source of employment in New Zealand. In 2009 80 plants employed 26,500 workers and the Silver Fern farmers co-op employed 7000 of these at

the peak of the killing season.

In the 1980s and 1990s a lot of processing plants closed down as new sanitary regulations came into force on the coat-tails of the UK entering the European Community in the 1970s and the

emergence of new ways of processing and refrigerating meat - a shift from whole carcass freezing to finished joint chilling.

The shift from old to new plants also allowed the strong packers unions to be undermined and allowed the introduction of new technologies such as automatic saws to begin the 'disassembly'

of sheep carcasses on the killing lines (See Te Ara: Meat Processing and see

Cybèle Locke, Workers in

the Margins: Union Radicals in Post-war New Zealand, p.38 for the deserved reputation of freezing plant workers as trade union radicals in the 1960s. In that decade they accounted for 25% of

all strikes in the country.)

Howver, like many unions at the time, the local committes were fiercely opposed to women moving onto the killing lines. At Ocean

Beach three women took their appeal to the newly established Human Rights Commission and wonin 1980 although local union secretary, Tony Taurima said 'it would be a long time before any women

worked on killing chains at the works in spite of the decisions' (see Locke above p. 66).

A book on the closure of Ocean Beach was written by Michael Turner in 1984 called, One Muff Too Tough: Ocean Beach.

Significant numbers of Invercargill people commuted to Bluff to work - the author recalls ‘standing room only’ in the workers’ train that left Invercargill around 6.30 a.m. in the mid 1950’s to transport workers to Bluff and also connect with the 8.00 a.m. departure of the Stewart Island ferry Wairua ‐ the first of that name.

(Invercargill City Council, BLUFF – Issues and Options,July 2012 p.3)

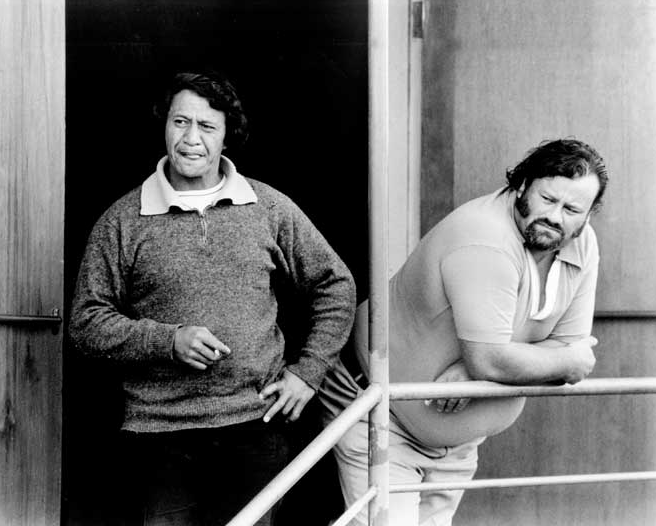

Funnily enough, after adding the last few items on this page a strange thing happened. I was out cutting back some trees on the lane I live down in Kent in the UK when a mountain biker comes toiling up the road. He either needed a breather or was curious to know what I was up to. Anyway he stopped and we got chatting. He was a rangy bloke, with a craggy face that looked like it has seen a lot of life. His accent seemed a compression of British port life and he exuded that happy go lucky confidence that would keep him one step ahead of life.

We got on to the coming winter, the fading light, the predictions of months of rain and he gleefully said that he was off out of the UK in a month to head for Goa, which was dirt cheap, and

Thailand for the winter. I mentioned I'd been to New Zealand and he immediately perked up and lifted up his mud stained dark glasses. When I mentioned I'd been down to Bluff and across to Stewart

Island he launched into a long tale about being a merchant seaman on the 'Kiwi coast' as he called it. He'd work on refrigerated boats taking lamb up to the Middle East - Basra and other ports in

the Gulf - and then coming back via Karachi or Bombay. Back in New Zealand they'd often be in port or moving between ports for two months. He remembered calling into Bluff and the meat

loading chutes on the quayside.

The visiting boats became an essential part of Bluff's drinking and partying scene. The local pubs would close at 6 o'clock of an evening and drinkers would come to the boats. From what he said

the crews set up bars and partied with the locals into the night. He recalled how they used to put out the pontoons they used when tied up to paint the ship's sides. These would be hoisted down

on the blind side of the boat and all the duty free booze that had been taken on board elsewhere was stacked on them to hide them from the customs inspectors. He'd loved working the Kiwi

coast, it was a party all the time.

The five loaders above were brought into use in 1963 and were the first of their kind in the world. They consisted of boxed in conveyor belts and greatly speeded up the loading of lamb and mutton

carcasses.

The five loaders were designed to carry whole lamb and mutton carcasses, each up to 27 kilograms (kg) in weight. The maximum capacity was 2100 carcasses per hour per machine.

Cartons of offal up to 40 kg weight each, and other packs of suitable shape, can be carried in alternate conveyor pockets at a maximum rate of 1050 packages per hour.

The loaders are designed to operate in winds of at least 72 kilomtres per hour (kph), and when stowed to be stable up to 170 kph. Storm anchors are fitted to prevent movement along the wharf. The

travelling ship loaders are capable of loading into the holds of any of the standard refrigerated ships that come to New Zealand (IPENZ Engineering Heritage).