The Barents Sea and Lofoten Fishery

To start at the beginning: driving along the lonely road that runs along the east coast of the Sørfjorden some 50km south east of Tromsø I passed through tiny hamlets and noted abandoned fishing boats and houses and old graveyards and even happened upon a funeral procession down a cold valley to the Gravlund (cemetery) whilst the bell in the wooden church tolled out across the country.

The road goes on a bit (about 50km) and for what seemed like hours I saw neither car nor person. Tiny seared fields struggled out of the snow and the dwarf woodland of silver birch, willow and the occasional stunted Scot's Pine hung to the steep fjord sides and gave way higher up to low junipers, lingon berry and other tundra-like plants and lichens. At one point I passed under fierce hanging boulders and a sign that warned of 'Rekkverk Mangler'(which Google translates as 'Handrails Missing') by a huge slew of fallen rock.

The road surface changed and I felt I was nearing its end. A wooden house stood desolate and stripped of all colour, an ancient rusting blue Volvo jutting out of a little copse of birch and the road pushed up over a tongue at the valley's end showing huge glacial deposits on the shore opposite the neck of the fjord. Then a quarry that practically ate up the road and I was on the north coast of an inlet arm of the fjord with the huge, wild, snow encrusted peaks of the Lyngen Alps disappearing into the scudding clouds.

Further on, and very much like a road on the north shore of the Applecross Peninsula on the far north west coast of Scotland, the route curled around a buttress and gave views of a sheltered bay

with two modern small fishing boats moored in the still waters. Down in the bay the ubiquitous Scandinavian red sheds perched by the water's edge with their wooden jetties. I stopped by one where

the strange sight of hundreds of two to three foot split cod hanging by the tail from a netted wooden framework caught my eye.

To me as a Brit conditioned to think in terms of mild wet winters it seemed bizarre to be hanging fish outside and open to the skies in the winter. But, of course, this was not Britain, but the Norwegian Arctic Circle, and the fish hanging on the hjell were the famous 'stockfish' - from the Danish 'stokvis' for 'stick-fish' - that are one of the oldest preserved foods known to history.

Later we saw the macabre shapes and withered, darkened skins of the stokvis hanging from barns and front porches higher up the Lyngen Peninsula and we came across vast hjell (stokkr in Old Norse) frames at Husøy on Senja Island where thousands upon thousands of stringed fish heads were hanging to dry with neither roof nor netting and a great congregation of hooded crows and gulls were gathered to pull of flesh and gouge out eyes as the snow fell and the clouds obscured the rocky spectacle we had come to see.

I assumed naively, ethnocentrically, that these strange fish were something like the great sheets of frosty white bacalao (salt cod) (which actually comes from the Flemish for stockfish - kabeljauw (cabbelau) see Wubs-Mrozewicz in Beyond the Catch, p.192) I had seen years ago in the waterfront stores of Lisbon. But they are not. Stokvis (which seems so much more evocative than the English 'stockfish) are air dried and fermented in the cold - but not too cold - dry winters and springs of Northern Norway.

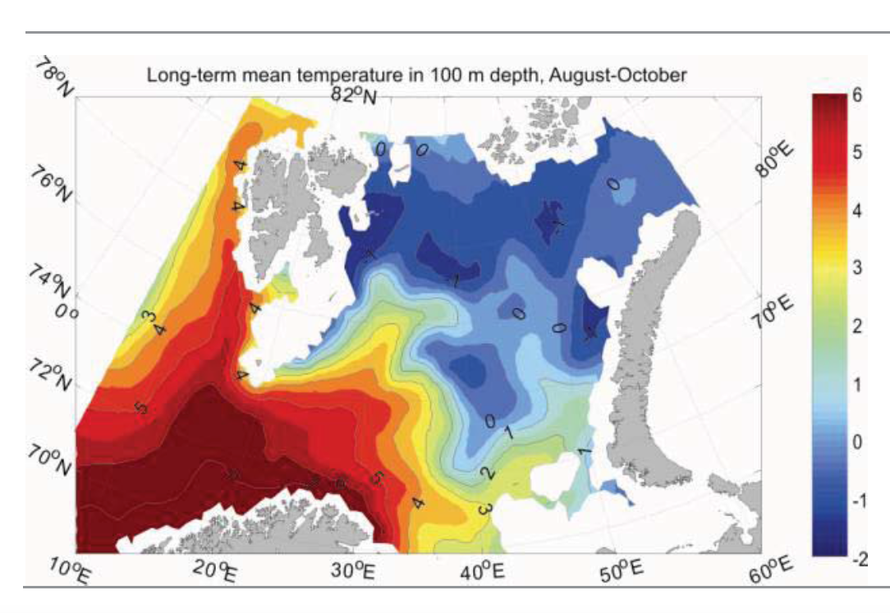

Too cold and the fibres of the fish freeze and break down. Too wet and mild and the rot sets in. But with the with the prevailing south westerlies and Arctic blasts and a temperature hovering around 0 degrees C the ideal conditions are created to slightly ferment and desiccate the thick slabs of cod on their 'hjell' before being stacked in airy sheds to finish off the process.

Drying time is usually three months after which the stockfish are packed in hessian bales. Saithe, ling, tusk and haddock can also used for production of stockfish. June 12 was the traditional 'fish-fetching day' in the Lofoten Islands. The fish are roughly sorted into three categories:

- Prima

- Sekunda

- Africa

Subsequently, it is sorted into a whole host of varieties, up to 30, according to quality, thickness and length.

Stockfish gets pretty tough and needs to be broken up with hammers. In the 16th century a German mill was invented - a Stockfischklopffer - to pre-soften stockfish which was a help to the Icelandic trade as its dried cod was harder than the North Norwegian variety (Wubs-Mrozewicz in Beyond the Catch, p.197).

In 1994, 4,824 tons of stockfish were exported at a value of NOK 392 millions. Most - three quarters - goes to Italy while the cheaper grades go to Nigeria and other African countries.

Once dried in this manner stokvis could be kept for seven years although its nutritious content declines rapidly after three years. Dried cod consists of 79% protein and almost no fat. For the Arctic Norwegian facing long periods of acute food shortage this proved a huge boon. And for seafarers setting out on voyages of discovery and plunder the light, portable and easily prepared dried cod was something akin to the freeze-dried rations carried by special forces the world over.

But also and beyond sheer survival in this process lay the possibility of turning a highly perishable commodity that came available in periods of vast glut and over-supply into a light, non-perishable and tradeable commodity.

Think of the vast schools of cod that migrate out of the Barents Sea in the late winter and early spring to spawn along the North Norwegian coast in general and the Lofoten and other islands in particular. This was a huge bonanza if it could be got and if something could be done with it.

Now to access the remote open-seaward facing fishing villages of Gryllefjord, Senjacopen and mountain-surrounded Husøy Norway's civil engineers and oil surpluses have constructed a fabulous set of perilous roads and dark dripping tunnels so that big, refrigerated and articulated lorries can collect frozen and processed fish irrespective of terrain and weather.

But back in the day when marine technology was in its infancy getting to sea, bringing home a catch and doing something with it other than watching it rot or fertilise the almost non-existent cultivable land required huge ingenuity and experimentation.

A recent book, Beyond the Catch: Fisheries of the North Atlantic, North Sea and Baltic (Brill, 2009) has brought together historical essays on the early and late Middle Ages fisheries of Europe. It organises itself around the concept of 'expanding fish horizons' that has two dimensions. One is the shift and extension of fishing from a freshwater activity to an initially coastal and later deep- and salt-water one. And the other is the distance that landed fish and fish products travel from their place of landing to their eventual market and place of consumption.

In the introduction the editors of the collection, Sicking and Abreu-Ferreira, argue that until the end of the first millennium CE (that's 'Common Era' instead of 'AD') most fishing activity was based on freshwater sources. This was not the case in Northern Norway where coastal fisheries were close to the land and where there were few alternative sources of nutrition.

But with the passing of the millennium fishing attention turned to the seas. Furthermore, marine technology allowed a gradual extension of fishing activity from small hand-powered open wooden and hide boats - the dory, the skiff, the curragh, - to larger open, wind-powered boats - the Nordland færing, åttring and fembøring - that could travel further from the shore with increasingly sophisticated fishing gear - nets, lines, ropes, floats, weights and hooks.

At the same time, the development and adaption of preservation techniques - air drying and dry and wet salting - allowed fish to be traded to inland entrepots, and eventually overseas to growing urban settlements and the developing markets of Catholic Southern Europe. It also meant that distant fish-rich waters - the huge accumulations of Cod on the Grand Banks off Newfoundland, for instance - could be caught and processed locally on the North American shore - before being transported back as light, stackable and non-perishable 'product' to home and other markets.

It seems that the original Norwegian stokvis trade was initially centred on Bergen in south-west Norway - so much in fact that in the Middle Ages (1360-1560) Berghervissch 'Bergen fish' was synonymous with stokvis - which climatically is not ideal for production - and became a target of the Hanseatic League which pretty much ran and organised the city's trade.

Most of the stockfish, in fact, was shipped down the Norwegian coast from the Lofoten and Vesterålen Islands between May and August and later from Iceland (see Wubs-Mrozewicz in Beyond the Catch, p.190) and was often used to trade for grain which was in very short supply in west and north Norway (ibid. p.193). The fishermen were Norwegian (nordfarere) and the traders North German Hansards. It is estimated stockfish exports in between the 14th and 16th centuries rose from 1,000 to 2,000 tonnes annually (ibid. p.204). At a possible multiplier of 4.4 based onthe protein content of stock and wet cod that would equate to be between 4,400 and 8,800 tonnes of fresh fish.

Cod stokvis also powered the Viking expansion into the West Atlantic and a transfer of fishing technologies to the countries and regions they settled in.

A similar process was taking place with herring as happened with salted and air-dried cod. This trade and processing technology of wet salting in barrels that kept the fish for two years seems to have expanded out of Scania in southern Sweden and expanded to Denmark and the Low Countries before crossing the North Sea to England and Scotland.

Recent archeological excavations in London have found evidence of a sudden increase in imported preserved cod in the 13th century which appears to have come from Northern Norway

The development of salt-water fishing had all sorts of consequences. New forms of temporary and permanent settlement became possible. Farmers would move to the coast in Denmark, for example, to live in temporary houses to exploit the herring run that became fish camps - fiskelejer. In the autumn merchants from Northern Europe gathered into proto-towns in the Scania fairs to purchase and organise the export of salt herring. With up to 10,000 boats involved these activities had a huge influence on the location and process of settlement and urbanization in the thirteenth and fourteenth centuries.

The settlement of Norther Norway is not covered in Beyond the Catch but the transformation of the seasonally super-abundant but highly and rapidly perishable cod into a tradeable commodity presumably encouraged the expansion of coastal communities - which often coincided locationally with what cultivable land there was - but also allowed new coastal communities to spring up where before lone and marginally sustainable farmsteads were only conceivable.

The relative inaccessibility of fjord-side and island locations was compensated for by their proximity to coastal and off-shore fishing grounds and the rapid development of marine technology. The development of a money economy also meant that capital could be accumulated and exchanged for better built boats from areas with a supply of good shipbuilding timber -something that lacked for climatic reasons in Arctic Norway. Vaager on the Lofoten Islands became the central market for the cod fish trade in Northern Norway and was founded by king Oystein (1103-1117).

Fishing before the 20th century was often a part-time occupation combined with farming in coastal regions that took place when cod visited Norway's coastal waters in the spring - January to April. Since then the development of larger vessels and deep-sea fishing has changed the picture hugely. Back in the 1930s fishing accounted for 15% of Norway's exports by value and there were 102,000 fishers. In 2002 these figures had reduced to 6% and 19,000 respectively.

As elsewhere in Europe, fishing has an important social policy role and has been vital for the coastal communities of Northern Norway.

Fishing's 'social policy objective [was defined as] the backbone in securing employment and settlement

in coastal Norway.' (Changing Attitudes p. 3 below).

As part of this social policy over-fishing became an issue and as fish prices rose less rapidly than Norwegian wages state subsidies were used to bolster fishing incomes and maintain employment in coastal regions. In 1980 subsidies accounted for 32% of the first- hand value of fish landings.

This level dropped to 12% by 1988 and was gradually phased out through the European Free Trade Agreement in 1989. Presently subsidy levels are below 1% (see this report on Changing Attitudes to Norwegian fisheries management between 1972 and 2012 p.6).

The geographical location and concentration of the industry also makes it extremely important for key areas of Norway's population, and particularly the three northernmost counties, Nordland, Troms and Finmark.

The location of the industry is very much concentrated regionally. Four of the 19 counties had

72% of the registered single-occupation fishers in 2002, of these, 48% lived in the three northern counties.

... This means that fisheries are a fundamental factor behind the population in the northern areas.

Many communities are totally dependent upon fishing and fish processing. Also in many small communities we still find the traditional combination of one single buyer/processor supplied by a number of small local vessels. Thus, fisheries policy in Norway is very much influenced by regional considerations and the aim of keeping small fishery communities alive. (Emphasis added, OECD Country Note on National Fisheries Management Systems in Norway 2002 p.9).

Historic photos of Jøvik from North Troms Museum

Between 2001 and 2014 the percentage of active number of vessels of the total Norwegian active fleet (which reduced from 8,000 to 5000 vessels) accounted for by the three northernmost counties of Norway - Finmark, Troms and Nordland has remained constant at around 36% with a slightly higher representation of vessels earning above (rather than below) NOK 50,000 at 2014 prices.

One of the things that really struck me in my travels around Tromso , the Sorfjorden, the Ullsfjorden and our trip out to the fishing villages of Senja Island was the variety of boats in the fishing fleets and the difference in size of the various fish processing plants we saw as well as the traditional salting and air drying of stockfish.

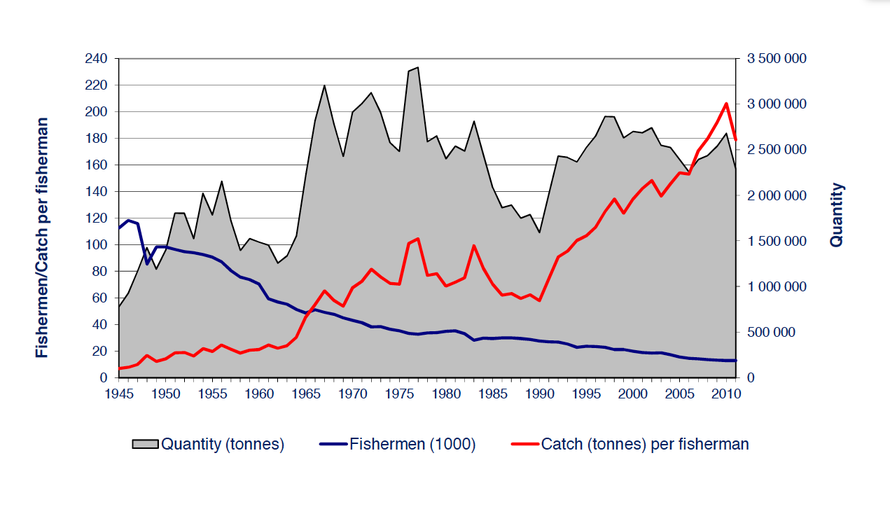

The above chart neatly summarises the dynamic of the Norwegian fishing between 1945 and 2010.

- The number of fishermen has decline from over 110,00 to below 20,000.

- The overall catch has grown from 600,000 tonnes to to about 2.4m tonnes

- The catch per fisherman has grown from less than 10 tonnes to about 180 tonnes.

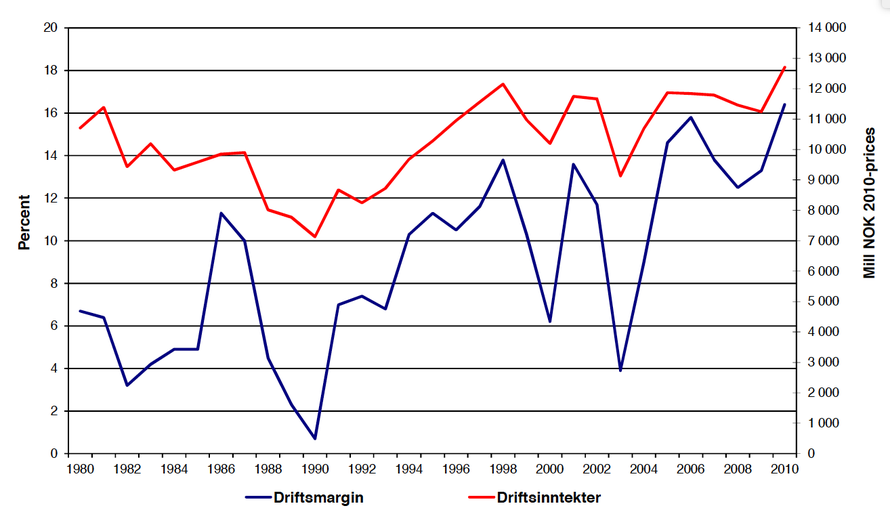

The chart below shows the overall revenue of the Norwegian fisheries that reached NOK 13bn (£1.1bn) in 2010 and the fluctuating operating margin that goes from just over 6% in 1980 to a high of

16% in 2010.

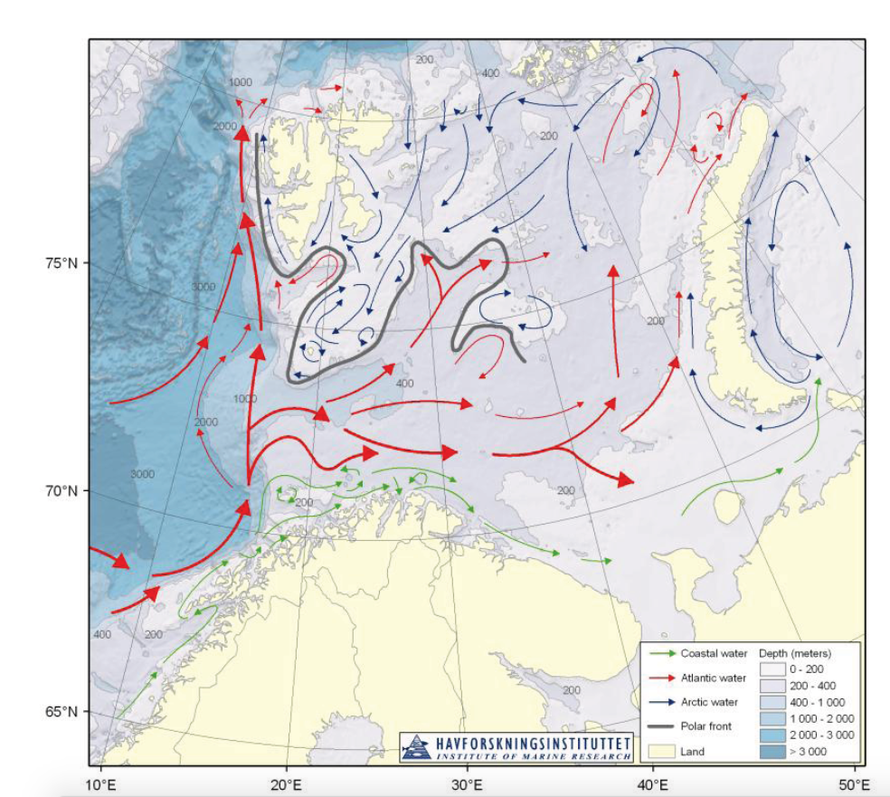

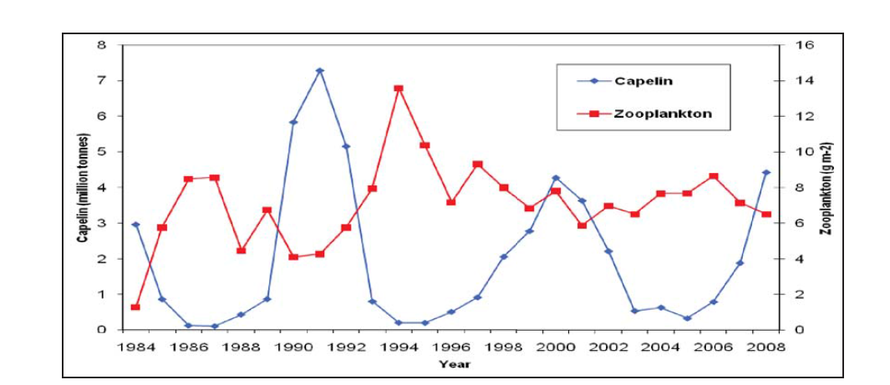

Fishing peaks with the phytoplankton bloom in the Barents Sea and Lofoten area in July, August and September. The phytoplankton bloom in July creates a zooplankton boom which attracts fish and in turn seals (and whales?)

Arneberg, P., Korneev, O., Titov, O., Stiansen, J.E. (Eds.), Filin, A., Hansen, J.R., Høines, Å.,and Marasaev, S. (Co-eds.) 2009. Joint Norwegian-Russian environmental status 2008 Report on the Barents Sea Ecosystem. Part I – Short version. IMR/PINRO Joint Report Series, 2009(2), 22 pp.

The Barents Sea and Lofoten Fishery

The Barents Sea is home to one of the largest concentrations of seabirds in the world [30 breeding and overwintering species including northern fulmar, black-legged kittiwake, razorbill, Atlantic puffin and common guillemot which show declines in the western Barents Sea], a diverse assemblage of marine mammals, including polar bears, and several commercially important fish stocks, the largest of which are Northeast Arctic cod, capelin and haddock. In addition, the Barents Sea is a nursery area for Norwegian spring spawning herring, one of the largest fish stocks in the world.

There is also a rich community of benthic animals in the Barents Sea, numbering more than 3000 species, as well as a diverse community of zooplankton. Planktonic algae and algae attached to the

sea ice both contribute to primary production in the region (Joint Norwegian-Russian environmental status 2008 Report

on the Barents Sea Ecosystem. Part I – Short version).

Capelin is a key species in the Barents Sea ecosystem. This fish species feeds in the marginal ice zone and spawns near the coast in the southern part of the Barents Sea and thus transports large amounts of energy from the north to the south. It is important as prey for several species of seabirds, mammals and commercially important fish stocks, in particular North-east Arctic cod and juvenile herring. (From Joint Norwegian-Russian environmental status 2008 Report on the Barents Sea Ecosystem p.7).

There have been three population collapses in the Capelin stock between 1984 and 2008 with peak stock at 7.5m tonnes in 1991 and minimum of less than 1m tonnes in 1987, 1994 and 2005. This may be caused by increased predation of capelin larvae by cod and herring due to fluctuating sea temperatures and sea ice coverage.

The anthropogenic driver with the largest documented effects on the Barents Sea ecosystem is

currently fisheries. Negative impacts of fisheries include overfishing of several of the smaller

stocks and damage to benthic communities caused by bottom trawling (Joint Norwegian-Russian

environmental status 2008 Report on the Barents Sea Ecosystem. Part I – Short version.p.8).

The report concludes that fish stocks of cod, haddock and capelin are sustainable and increasing whilst some other smaller stcoks of Greenland halibut, golden redfish, deep-sea redfish and

coastal cod on the

Norwegian coast are at 'low levels'.

Cod is the top predator in the fish ecosystem and has not been replaced by prey species - such as herring and capelin - as appears to have occurred in other Atlantic cod fisheries that have struggled to recover even with a fishing moratorium.

However the development of large-scale industrial fisheries is having an impact on cod sizes and,

this means that the Barents Sea is now likely to be more susceptible to large outbreaks and fluctuations in the stocks of small pelagic schooling fish such as capelin and herring [so-called 'prey fish']. Thus the situation might have evolved to become more similar to that in other northern shelf ecosystems. (Joint Norwegian-Russian environmental status 2008 Report on the Barents Sea Ecosystem. Part I – Short version.p. 15).

Sea temperature rises caused by global warming could have negative impacts by paradoxically increasing the rate of herring recruitment (i.e. survival). An increased herring stock could have negative impacts on capelin survival (through egg and larvae predation) which is turn can affect cod stocks through less available prey fish and more cannibalism within the cod stock. This in turn can impact on seabird and other populations. (Joint Norwegian-Russian environmental status 2008 Report on the Barents Sea Ecosystem. Part I – Short version.pp.15-16)

Norwegian quota sizes for 2012 in the Barents Sea were as follows:

- North East Arctic Cod 339,857 tonnes

- Haddock 153,253

- Capelin 221,000 tonnes.

- Halibut (total Norway/Russia quota) 18,000 tonnes.

Excluding halibut that is a total Norwegian quota for cod, haddock and capelin of 714,110 tonnes.

The Norwegian quota figures for 2012 compares with total EU 2012 EU quotas of

- Cod 178,745 tonnes

- Haddock 61,734 tonnes

No wonder Norway does not want to be covered by the EU's Common Fisheries Policy!

Norway experienced dramatic effects on fisheries and coastal communities due to overfishing and the subsequent collapse of the large Norwegian spring spawning herring stock in the late sixties (p.1 below).

In terms of compliance with the UN Code of Conduct for Responsible Fisheries Norway scored the highest but achieved a compliance score of only 60% in 2009. In an evaluation of progress in

implementing ecosystem-based management of fisheries (EBFM), Norway ranked second after USA, with an overall performance score of slightly above 60 %. However, whilst scores for performance

and principles and EBFM indicators were high,

they were less for EBFM implementation (see this report on Changing Attitudes to Norwegian fisheries management between 1972 and 2012).

The Qaqqatsiaq, 100 per cent owned by Royal Greenland Group, is a shrimp trawler. It is an ice class trawler certified to fish in polar waters and fishes 24 hours a day

throughout the year in the sea to the west and north west of Greenland. Shrimp and prawns are sorted, cooked, packed and frozen on board within three hours of their being caught. There is a 25

man crew (and it looks from port stops that they work two month stretches). The ship is 73m long and has a 7500 horsepower engine. Royal Greenland has 11

packing plants in Greenland.

There are a couple of Royal Greenland videos showing ship working and shrimp processing onshore at the end of this page.

Atalantic shrimp trawling if often done using a double rig (two nets) with a grid and fish escape hole to reduce by-catch. Massive trawl doors (otter boards) are used to keep the nets on the sea bed and to keep the nets open.

Their use is controversial due to the damage they can do on hard ground and to the mud they release into the water column which can cause reduced light

levels, algal blooms and can stir up pollutants that have settled into the sea bed.

And in case you thought it was all fish and snow here is a grand video from Senjahopen featuring Andreas Løvold. This seems to be from a Norwegian TV series called Yttersia.

And this classic 'Fish & Potatoes' (Fesk & Potedes) is a re-edit of the north Norwegian hippie band 'Boknakaran' by Rune Lindbæk, and was released on Idjut Boys' Noid Recordings. Original lyrics by Helge Stangnes. Video editing by Tösch.

And this is a video of the old fishing days on the Lofoten Islands. Note the fantastic 'viking' style rowing boats so low in the water.

Note: Norway also produces and export bacalao (clipfisk - slated cod and other whitefish). In January 2015 exports were worth NOK 444m for the month alone with most of the fish exported to Brazil

(see Northern Seafood).