Brief History of Cape Towns Townships

Uitvlugt /Ndabeni (1902)

The first segregated township to be developed by the white authorities was Ndabeni in 1902. Bubonic plague had broken out which was soon blamed on ‘these uncontrolled Kafir hordes’ and many whites demanded segregation. Apparently, the Cape Town Medical Officer for Health declared that the living conditions of Africans were ‘very undesirable, both from the point of view of sanitation and socially, by bringing uncleanly, half-civilised units into intimate contact with the more cleanly and civilised portion of the community".

Uitvlugt (later known as Ndabeni) was established on the Cape Flats, next to a sewerage plant. Between 6 000 and 7 000 people were forcibly moved from District Six, by the city’s docks, to Ndabeni. It was a Coloured rather than Black African township being comprised of ‘Hottentot, Malay and mixed races’.

The township comprised 5 large dormitories each housing 500 men, and 615 lean-to huts made of corrugated iron, without floors, which often flooded in the

winter rains. Washing and cooking facilities were public and inadequate, and the grid-like streets were patrolled by African constables (see Capetown

At).

Map showing forced eastward migration away from Cape Town of Coloured and African populations from District Six, through Ndabeni (1902) to Langa (1923), Nyanga (1946), Mitchell's Plain (1970) and Khay

Langa (1932)

In 1923 Langa township was established 5km south east of Ndabeni, and Ndabeni was dismantled under pressure from nearby white residents at Pinelands. Today it is an industrial estate mainly occupied by the textile and clothing factories. (For above see Wikipedia: Ndabeni)

What emerged at Langa ‘was a design allowing maximum visibility of residents by the authorities and hence their control. No visitors or gatherings were allowed

without permission from the superintendent, and the brewing of sorghum beer (utshwala) was prohibited' (see Capetown At).

In 1923 the Native (Urban Areas) Act was passed restricting the entry of Africans into the city. This deemed urban areas in South Africa as white and required all black African men to carry passes was replaced in 1945 by the Natives (Urban Areas) Consolidation Act, in 1945, which imposed essentially the same conditions. The Natives (Abolition of Passes and Co-ordination of Documents) Act, was passed in 1952 and required all black South Africans above the age of 16 to carry a pass at all times when in white areas.

When someone came from the Eastern Cape they couldn’t stay here [Nyanga] before they had gone to Langa

to be dipped. When they came through the join? (labour recruitment) they first had to go to Langa to be dipped before they could mix with other people. They were dipped like cattle (see popularmemory.org.za).

Nyanga (1946)

(Xhosa ‘moon’) is one of the oldest black townships in Cape Town. It was established in 1946 with 210 houses. In 1956 it was enlarged to include the Nyanga Transit Camp and the settlement of Mau Mau. The weekly rent for a house was 7s 6d compared to that for a shack of 6d and many people remained in shanty towns.

Nyanga is made up by eleven townships (Lusaka, KTC, Old Location, Maumau, Zwelitsha, Maholweni"Hostels", Black City, White City, Barcelona, Kanana & Europe. In 2001 it had a population of 58,452 of whom 99.54% were African and 50% of the housing units (13,734) were informal dwellings (Capetown.gov).

Nyanga is one of the most dangerous townships in Cape Town.According to data collected by the South African Institute of Race

Relations (SAIRR) over 700 people were murdered in Gugulethu between 2005 and 2010. "This amounts to one murder every two-and-a-half days for five consecutive years." In 2011 murders were

down from previous year’s 217 to 198. Cape Argus. (There were 619 in the whole of the UK in 2011). Nyanga is situated 26km from Cape Town

near to the international airport and next to the townships of Gugulethu and Crossroads.

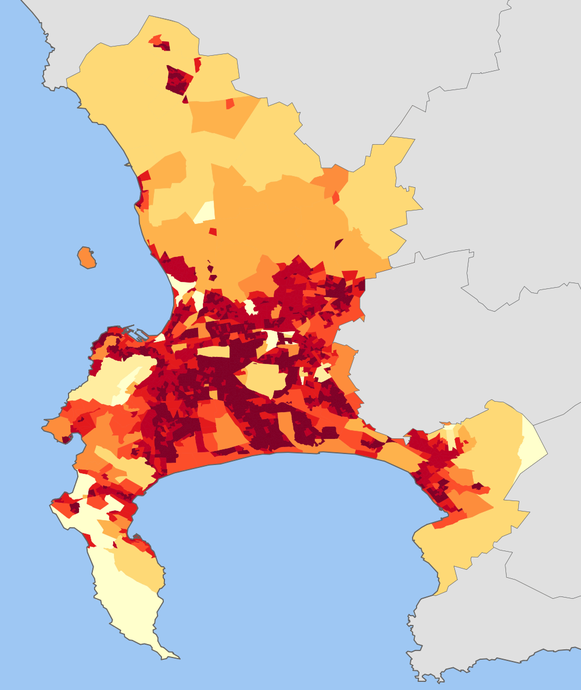

Map showing population densities in Cape Town at 2001

Broad Estimates of Township Population Densities (People per km2)

- Nyanga 17,000/km2 (45,000/sq)

- Gugulethu 13,000/km2 (33,000/sq mi)

- Khayelitsha density 7600/km2 (20000/sq mi)

- Mitchell's Plain 4,400/km2 (11,000/sq mi)

Source: all from individual Wikipedia pages but references don't work or don't tally.

Crossroads (1970s)

In 1952 the government' imposed 'The Prevention of Illegal Squatting Act' which forced local authorities to set up emergency or Transit Camps where people

could be concentrated and controlled, and permitted authorities to destroy illegal shacks.

In the late 1950s the destruction of shack settlements increased in areas like Hout Bay and Elsies River. Over 5000 so-called 'bachelors' were forced to move into hostels, and thousands of

'illegals' - most of whom were women - were 'endorsed out' of the city back to the Eastern Cape.

In 1959, despite an outcry from employers, the Native Affairs Department decreed that no more Africans could be employed in Cape Town. At the same time, the conditions in the Eastern Cape were

deteriorating and migrant labour was one of the few lifelines for many families.

The local government continued to clear squatter camps through the sixties and seventies. The Modderdam squatter camp was destroyed by two bulldozers during one week in August 1977. Many

squatters moved to Crossroads and by 1977 there were 18,000 living there. Despite attempts close down Crossroads the government was forced to recognize it as an ‘emergency camp in 1978 and

install rudimentary water supplies and refuse collection.

In 1983 bloody violence broke out in Crossroads and growing tensions between the ‘comrades’ of the United Democratic Front and some residents led to the rise

of the police-backed and armed ‘witdoeke’ (who wore white armbands) who set fire to all the Crossroads settlements and left 60,000 people homeless (see Cape Town

At).

Mitchell’s Plain (1970s)

In 1966 the government declared District Six in inner city Cape Town a ‘whites only’ area and despite tenacious resistance by 1982 more than 60,000 people had been relocated to the Cape Flats and Mitchell’s Plain and the district had been flattened by bulldozers (see District Six Museum).

Mitchell’s Plain was designed as a Coloured Township for middle-income families but by the late 1980s much of it had been reduced to ghetto areas where gangsterism and drug abuse were rife. It has a population of over 300,000 in 2001 of whom 84.2% are Coloured and 14.9% Black African. There was unemployment of 30% in 2001 which rates of between 60-80% in the northern and scattered western parts of the township. (See Wikipedia: Mitchell’s Plain and Cape Town Gov).

Mitchell’s Plain has large retail developments in the Central Business District and in shopping centres.

Video of photographs of Khayelitsha and Langa townships with great soundtrack and interesting notes

Khayelitsha (1985)

The authorities created Khayelitsha in response to the immense pressures for some kind of home from migrants moving to the Cape and from those forced out of Crossroads by the witdoeke violence. Initially planned as four towns of 30,000 people with 4150 serviced plots (water and toilet) and 13,000 rented small block-built houses by 1990 the population had mushroomed to 450,000. Unemployment was 80% and 86% of the population lived in serviced or unserviced informal dwellings. Pressures on Khayelitsha only grew after the 1994 election of an ANC government as influx controls were abolished. Khayelitsha had a population of 406,000 in 2005, of whom 40% were under 19 years of age.

The anti-eviction campaign at Joe Slovo informal settlement at Langa 2007-9

The struggles over housing (there is a 400,000 unit shortage of housing in Cape Town alone according to Jeanne Hromnik below) continue. Residents at Joe Slovo informal settlement (estimated population 20,000)at Langa township resisted forceable relocation to Delft township 34km north east of Cape Town in 2007.

Some of the day to day development of the struggle is published on the Abahlali baseMjondolo website here. In a nutshell, and according to the Abahlali baseMjondolo website, the national Housing Minister Lindiwe Sisulu was intent on evicting residents of Joe Slovo informal settlement to distant Delft at a rate of 100 families per week for the 45 weeks (4,500 families) despite her assurances that this was not the case.

This was in order to redevelop the land at Joe Slovo by building 'bond houses' (ie houses for sale) at a price to residents who could afford them of between R150 000 to R250 000 for a house. These will only be able to accommodate 1000 people. It is highly unlikely that any of the current familines in Joe Slovo informal settlements will be able to buy one of these. This redevelopment is part of the so-called N2 Gateway project which is being run by 'a partnership of the banks, the BEE [Black Economic Empowerment] capitalists of the N2 Gateway and the government' (Joe Slovo Committee - Anti-eviction Campaign Press Statement 02/09/2007).

Residents feared that they would be dumped in Delft without proper housing, ending up in Transit Camps like Blikkiesdorp or "Tsunami" and unable to access central Cape Town and the work opportunities there. They ideally wanted the Joe Slovo land to be redeveloped with Reconstruction and Development Programme (RDP) houses.

RDP houses are allocated through a waiting list and are free. There is a huge housing waiting list of 322 619 in Cape Town (see here for details and allocation procedure). Applicants must be over 21, South African citizens, have an income of less than R3,500 (£274/€348) a month, be married or live with a partner or be single and have dependent children and have never owned a house or a property anywhere in South Africa. To extend or renovate an RDP house before eight years of ownership residents must get permission to do so from their local municipality (see Property24).

RDP houses have 36m/sq (joburg.org.za)(360 sq/ft) of floorspace or a room 20ft x 17ft (say a room and a half in a moderate semi-detached house in the UK). It is acknowledged that there is a gap between those who are allocated a free RDP house and those who can afford to buy on the open market. The Finance Linked Individual Subsidy Programme is supposed to cover this but some argue that it still leaves people unable to purchase on the oepn market (for a discussion see here).

Fierce protests followed with violent confrontations with the police and the blocking of the main N2 motorway into Cape Town. Close range rubber bullets and summary arrests were employed liberally by the police, according to reports.

The Cape Town High Court suspended the forced evictions for 9 weeks but upheld them all the same. The residents took the case to the Constitutional Court in Pretoria which ruled in 2009 'in favor of the eviction of Joe Slovo residents but only based on certain conditions including that 70% of homes built on Joe Slovo land be allocated to Joe Slovo residents, that government must enter into consultation with residents, and that temporary relocation areas where residents were to be moved be of higher quality.'

In August 2009, new Minister for Human Settlements, Tokyo Sexwale, placed the eviction of residents on hold and in September 2009, reports surfaced that the

Constitutional Court had quietly issued a new order suspending the eviction of Joe Slovo residents until further notice.

The N2 Gateway scheme has come in for much criticism for shoddy building and its treatment of residents from the Auditor General and housing rights groups (see Wikipedia: N2 Gateway)

Note: The development of RDP housing areas has not been without criticism in South Africa: 'Critics point to poor housing quality as the chief problem being faced. One research investigation in 2000 found that only 30% of new houses complied with building regulations. Critics also note that new housing schemes are often dreary in their planning and layout -- to the extent that they often strongly resemble the en masse bleak building programmes of the Apartheid government during the 1950s and 60s' (see Wikipedia: Reconstruction and Development Programme.)

And residents in Delft and the N2 Gateway housing scheme illegally occupied new houses, were forcibly evicted and rather than being relocated to a notorious Temporary Relocation Areas known as Blikkiesdorp (a ‘blikkie’ is a tin shack) occupied pavements for a year and half on Symphony Way (of all places).

A book No Land! No House! No Vote!: Voices from Symphony Way records their struggles and eventual relocation to Blikkiesdorp.

Blikkiesdorp was built by the City of Cape Town in 2007 by then Mayor Helen Zille. It contains approximately 1,600 one room structures built of corrugated iron. It is described by the pavement dwellers as `for pigs', a place where rapists live around the corner and drug dealing is rife. In appearance it is like a concentration camp and facilities are poor, with four families to one toilet and tin walls that let in both heat and cold.’ (For quote see review of No Land!)

Barefoot Workshop documentary of the Symphony Way struggle and forceable relocation to Blikkiesdorp

The Abahlali baseMjondolo (Shack Dwellers) Movement is an important organising force behind the struggle for Shack Dweller's housing and huamn rights. 'Although it is overwhelmingly

located in and around the large port city of Durban it is, in terms of the numbers of people mobilised, the largest organisation of the militant poor in post-apartheid South Africa' (see

here).

'The movement’s latest victory was announced in the hour of its greatest affliction. On 26 September, AbM’s strongest base, the Kennedy Road settlement, was attacked by armed militia, apparently acting with the support of local ANC structures. In the aftermath, houses of AbM supporters have been destroyed, 13 members imprisoned and death threats forced its leaders into hiding (see article ‘The attacks on Kennedy Road’). Amnesty international has expressed concern over “the apparent unwillingness of the relevant authorities in investigating these crimes” and official comments, which “could have the effect of inappropriately criminalising a whole organization and making its members vulnerable to threats of violence” (see here).

A recent report on the website details ongoing problems in Langa:

'This is the story of Thandeka Ngcelwane who, last week, was allocated No.59, a government built shack in Langa Temporary Relocation Area. However, while she was away from her new home for a few hours to visit her brother, the TRA committee headed by Zukisani Sibunzi broke the lock on her door and put someone else in the home. When she returned she found a lady in her home and her belongings removed – Thandeka had been illegally evicted from her home and, since her old shack in Joe Slovo was now demolished, she was left with nowhere else to go.'

This speaks to widespread corruption in housing development and allocation that has blighted recent years.

(On corruption see this DfID UK report :

'The [...] examples illustrate the typical problems and successes that emerge from housing provision in terms of the People's Housing Project model and more conventional housing approaches. The problems of poor construction, project disruption (community conflict, theft and vandalism) are common to both conventional and PHP approaches. ... In general, though, the policy imperative to use emerging contractors or beneficiary-owned and beneficiary-driven project approaches, while laudable in its developmental motives, in fact introduces an increased likelihood of poor construction and community conflict. Such an environment proves to be corruption-friendly since cost cutting, project failure and beneficiary discontent can be blamed on a wider set of factors and the actual service provider can shirk accountability' p.54.

(in Corruption in Infrastructure Delivery: South Africa G. Hollands DfiD 2007. See also M. Rubin 2011 and this BBC report from 2008 and this South Africa.Info report).

This is all part of a more general malise recognised by the ANC at its five-yearly policy review in 2012. An internal discussion document stated,

“The erosion of the character and capacity of the movement and the hollowing out of the capacity of the democratic state must be reversed urgently and vigorously if we are to rapidly improve the pace and depth of transformation” (see FT 21/6/2012.)