The reviews of the Hilary Spurling Matisse biography at the time of publication were generally positive and the second volume won the Whitbread Prize. Jackie Wullschlager in the Financial Times is unreserved in her praise. John Elderfield, chief curator of painting and sculpture at MOMA, New York is more circumspect in The Guardian. He wants more art history and exploration of Matisse's creative process and less exposure to the master's, as he more or less puts it, interminable whinging.

Spurling is certainly fulsome in her account of Matisse's anxieties and troubles but he had a lot to be worried about and his times - he lived through three Franco-German wars - were anxious and tragic. That he did not succumb to collaboration - of which others have accussed him - or go into exile but doggedly kept on making his art as an antidote to barbarism (see for example the awful description of the Gestapo torture of his daughter, Marguerite) says a lot for his tenacity, which also kept him from embracing the widespread adulation of Stalin amongst France's post-war artistic and intellectual elite. Indeed, his slogan might have been, to paraphrase the old SWP mantra: 'Neither Russia nor Rome, but international luxe, calme, et volupte'.

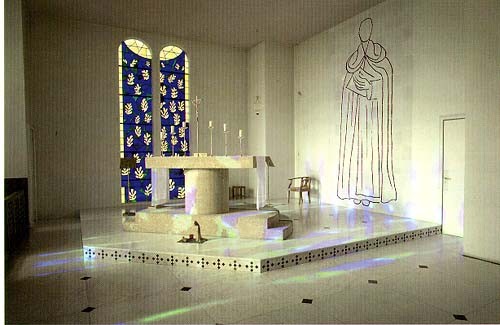

The book climaxes with Matisse's decoration of the purpose built chapel at Vence from his mobile bed-ambulance and his death shortly thereafter. His helpmate, love, carer, and business manager, Lydia Delectorskaya - who had devoted herself entirely to Matisse and his work and failing health for 15 years - picked up her packed suitcase and - her work done - left Matisse's household hours after his death.

One thing else that I learned from the book is that there is a Matisse Museum at Le Cateau Cambresis in the North of France, near the Belgian border, where he grew up. This was founded with a gift of 150 paintings from the artist. It's two hours from Calais.

Write a comment