I am reading Hilary Spurling’s 2 volume biography of Henri Matisse. It is a real revelation. I had somewhere along the way picked up the notion that his art had come to him easily, magically formed and flowing as easily as cool water from the base of a limestone cliff.

The story meticulously unfolded by Spurling from his huge correspondence and her tireless research shows an absolutely driven and obsessive man battling with himself, his family, his and their health and frequent derision throughout his career. Nothing can be allowed to stand in the way of his art and his ferocious desire to succeed against formidable odds. The martyrdom of his wife, Amelie, and children, Marguerite, Jean and Paul, in the cause of his art is at times shocking and yet he was capable of great kindness to them and his succession of young models.

Nor had I realized how he was reviled and mocked both by the art world of the Academy and Picasso and his cubist chums who at one time launched a graffiti campaign against Matisse on the walls of Montmartre (Vol II:64). When his paintings were first shown in Chicago in 1913 the students of the Art Institute of Chicago burnt copies of his works and staged a public trial for treason against ‘Henry Hairmattress’ (Vol II:136).

But the boy from the damp grey North East of France, son of seed merchants, was eventually to triumph and force new developments out of his failing health, often under the critical tutelage of his children who kept him from backsliding or falling into pastiche. At one point, tried beyond endurance Matisse, a hardened unbeliever, admits to praying what might be called the artist’s prayer:

Give me strength to resist, patience to endure, and constancy to persevere. (Vol II:352)

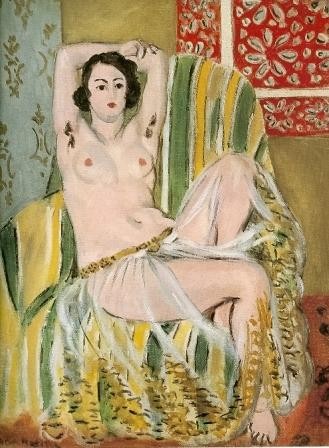

The book is also fascinating on Matisse’s relationship with his models – nearly exclusively young women in their late teens and early twenties. Spurling is adamant that there is no evidence of sexual involvement, predatory or otherwise, with the possible exception of Olga Meerson, a student of Matisse’s who was madly in love with him. But the relationship between artist and model, often long-lived as in the seven years Matisse drew and painted Henriette Darricarrere, was intense, mutual and solitary – says Spurling

In the seven years they worked together, Matisse multiplied variations on the same theme with ferocious audacity in paintings, drawings and prints. (Vol II:248)

Often his models became part of the family and there seems to have been little tension between Madame Matisse and their presence, even when, as often happened Henri was working in Nice and she was taking care of business in Paris. For more on this see Matisse and his models.

In this Spurling recounts the following:

Sex, in fact, was one of the things Matisse grumbled about having to do without in Nice. So far as modeling went, he applied the same rules to human beings as to a fish dinner. “I’ve never sampled anything edible that had served me as a model . . . ,” he explained, describing a plate of oysters brought for him to paint from a nearby café by a waiter, who later fetched them back to serve to his customers at midday. Matisse said it never occurred to him to tuck into his oysters for lunch: “It was others who ate them. Posing had made them different for me from their equivalents on a restaurant table.”

Perhaps what is most interesting, is the joint endeavor of artist and model working together, of finding a way of looking and being looked at intently that transcends the rage of lust, erotic possession and subjugation to find a kind of charged and attentive calm – Matisse’s great painterly goal – that allowed Matisse to portray the dignity, beauty and autonomy of the model.

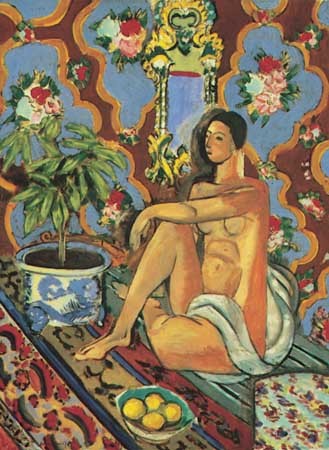

At the same time the social and sexual relations of early twentieth century Europe were hardly conducive to equality between men and women and I’m sure there are art historical analyses that castigate Matisse and his use of young women as passive adornment – like a plate of oysters - for his, and his gender’s, Orientalist fantasies.

Critical influences on Matisse’s art were the Islamic art of Spain and Grenada in particular and Russian iconography.

Hilary Spurling, The Unknown Matisse and Matisse The Master, Two Volumes, 2005 Hamish Hamilton

Write a comment