VII. The Banks: swollen deposits and reckless expansion

This is a series of detailed notes with the most recent additions at bottom of page

Cyprus's accession to the European Union in 2004 represented a 'big bang' for Cyprus's until then relatively parochial banks. Not only were they faced with new regulation and capital rules but also new opportunities.

In the domestic market EU regulation meant that funds were transferred out of the cooperative banking sector.

At this time both Laiki and the Bank of Cyprus had modest Greek operations and both had bold ambitions to expand into Eastern Europe and the Eastern Mediterranean.

The attractiveness of Cyprus to depositors - light touch regulation, low taxation, high rates of interest and Enlish law - gave its banks 'more to invest than they knew what to do with' (FT Jenkins/Hope 19 March 2013).

Laiki bank and Bank of Cyprus were involved in intense - some say 'pernicious' - competition to out-grow the other in the mid-2000s.

Both were hit badly by their massive expansion into Greek government debt as other pulled away from this increasingly toxic market. And both are exposed to losses in the once-booming real estate sector that 'accounts for about 40 per cent of each bank’s loan book'(FT Jenkins/Hope 19 March 2013).

Laiki Bank

When in power President Christofias secured a €1.8bn state bail-out of Laiki (Cyprus Popular Bank) and signed a €2.5bn loan from Russia. He undertook increasingly desperate attempts to find other non-EU sources of loans, including China, to no avail. When the public cash started to run out the government began to raid state-owned utilities for cash to keep the ship of state afloat.

On that initial Cyrpus bank bailout: Cyprus banks faced strong headwinds after the Greek bond haircut. They held of €22bn of Greek enterprise and individual debt. Their large holdings of Greek state debt resulted in a €3bn haircut following the PSI – private sector initiative – write down of these debts.

Cyprus Popular Bank (CPB) Laiki, the country's second largest, could not raise sufficient capital to cover its share of this loss - €2.3bn - (FT Hope, 15 May 2012 and 05.06.12) and a €1.8bn share issue (equivalent to about 12 per cent of the island’s GDP) was underwritten by the Cyprus government. (Popular's Greek management team resigned under pressure from the Cyprus Central Bank as they were held responsible for exposure to the Greek debt and for a sharp rise in non-performing loans in its Greek branches (FT Hope, 15 May 2012).

CPB's largest shareholders are Dubai Holdings (17-18%), the Greek-based Marfin Investment Group (which also provided the bank's senior management team) and the Cypriot family-owned Lanitis group (4-5%).

Popular was unlucky or imprudent or both because by being based in Cyprus it was not eligible for recapitalisation under a €48bn rescue package for Greek banks included in the country’s second bailout (FT Hope, 15 May 2012). For some reason Popular's Greek subsidiary Marfin Egnatia Bank Public Co Ltd was restructured to a branch in March 2011 thus shifting the liability for recapitalisation from the Greek to Cypriot authorities (see Gabriel Sterne 2012 background note at Exotix). In retrospect this looks like a disastrous decision (see also Wall St Journal on expansion into Greek markets.)

Leaked portions of the Alvarez & Marsal report (see below) emerged in April 2013. One leaked section that featured in the Cyprus Mail (Psyllides 5 April 2013) appears to have concerned the decision to convert Laiki's Greek holdings from a subsidiary to a branch.

Accroding the the CM report of the Alvarez & Marsal report the Central Bank of Cyprus had few powers under the current legal and regulatory framework to stop the cross-border merger between Laiki and Greece’s Marfin Egnatia.

“The structure of the regulation and legislation is such that under the Mergers Directive the bank did not require any authorisation from the CBC (Central Bank of Cyprus), this resulted in the bank being able to transfer the assets and liabilities to Cyprus without approval from the CBC,” the report said.

The CBC was left with one option, the firm said, either to accept the conversion of the Greek subsidiary or force the bank to cease operations in Greece.

“Given the desire to maintain the bank’s headquarters in Cyprus and the perceived regulatory benefits, the CBC notified the BOG (Bank of Greece) of the creation of Marfin Popular Bank’s branch in Greece.”

According to the report, revoking the approval could have had a significant impact on the Cypriot banking system as the CBC would have needed to set out the reasons for its refusal, such as the need to safeguard the interests of the depositors.

“Mr. Costas Poullis, former head of supervision at CBC, stated in his interview that revoking the approval for MPB [later renamed Laiki] to operate a branch in Greece, and therefore essentially terminating the bank’s operations in Greece, was not an option as it would have had a significant impact on the confidence of the banking sector,” the report said.

The Greek Marfin Egnatia brought €2bn in Greek Government Bonds to add to Laiki's €1bn and '€800m in loans to various entities for the purpose of investing in Marfin Investment Group (MIG), loans granted to the MIG group on favourable terms.'

The CBC required MPB to hold €1.56bn of additional capital against its sovereign bond portfolio and €2.1bn against its loan portfolio but this did not prevent the meltdown of the bank's position when the Greek haircut was announced.

The report states, “Based on the findings of the investigation, it would appear that the current regulation and legislation does not provide sufficient support to the CBC where a Cypriot bank wishes to convert an existing foreign subsidiary into a branch."

THE UK's new financial regulator, the Prudential Regulation Authority, ( a unit of the Bank of England) has decided that Laiki bank depositors in the UK will be covered by the UK's deposit protection scheme (up to £85,000 at least). This is being justified on the grounds that the Laiki UK banking operations are being rolled into the UK operations of the Bank of Cyprus, in line with the bailout in Cyprus. Laiki depositors with more than €100,000 on deposit in UK branches will not be subject to the haircut being visited on Laiki depositors in Cyprus (see Reuters Jones 2 April 2013).

This protection is being afforded even though Laiki's UK operations were run as a branch (rather than UK-based subsidiary) operation and were not covered by the UK deposit protection scheme (see FT Jenkins 2 April 2013). Laiki UK's 15,000 deposits are valued at £270m (Daily Telegraph 2 April 2013).

The FT says Laiki UK 'was popular because of the high interest rates it paid out on fixed bonds.' (see FT Jenkins 2 April 2013)

(For a detailed insider account of events at Laiki between 2011 and the bailout from Reuters see ekathimerini 2 April 2013).

The second March bailout agreement agreed to close down Laiki bank and create a bad bank of deposits over €100,000 to be used to pay-off the banks debts whilst the good assets and deposits under €100,000 were transferred to the Bank of Cyprus.

Depositors in Cyprus with over €100,000 at Laiki were predicted to be pretty much wiped out.

The FT has also drawn attention to the over-extension of Laiki in Greek bonds and corporate lending. It quotes Lambros Papadopoulos, an independent analyst,

“It got into trouble because of very aggressive expansion mostly in Greece. The balance sheet got overstretched and then Greece went wrong.”

It also refers to other analysts who say that Laiki’s move into the Greek corporate market was badly timed as it sought to expand just as recession hit (FT Hope 22nd March 2013).

Reuters produced a dramatic blow-by-blow account of events leading up to the effective closure of Laiki at the end of March 2013.

On March 27th 2013 the board members of the bank were informed by the Central Bank of Cyprus that they were being dismissed and replaced by a special administrator to wind down the bank.

The bank had lost €1.8 billion before tax in the first nine months of 2012 and €4.1 billion the year before. Its expansion into Greek government bonds resulted in catastrophic loss of €2.3b and bad lending decisions in the bank's Greek branch network took their toll.

In a desperate bid to find new private capital injections the bank eventually was forced to take a €1.8bn recapitalisation from the Cyprus government - a move which gave the state an 84% holding in the bank.

Seven new directors were appointed and they were shocked at what they found. Laiki was surviving on fortnightly renewable ECB emergency liquidity loans of €9bn channeled through the Cyprus central bank.

Plans were drawn up to sell assets, cut costs (staff were laid off in Greece and Cyprus and mobile phone use was restricted) and recapitalise the bank while ring-fencing its increasingly troublesome Greek operations.

But events were moving quickly. News began to emerge of a possible haircut on depositors in late 2012 as part of a bank bailout. Money began to leave the bank and as the bank's asset position worsened the European Central Bank informed the Cyprus Central Bank that it would not accept the share capital bought by the Cypriot state for €1.8bn as collateral against emergency liquidity assistance. Eventually Laiki pledged €20bn of collateral including all its premises in order to keep drawing down the ELA funding that was keeping it afloat.

This desperate situation continued until the conlusion of the Cypriot elections in February 2013 by which time the ECB was more than impatient to act.

Cypriot negotiators went to Brussels on 15th March to work out a settlement with the troika and the eurozone finance ministers group. On the following Monday Laiki directors were told that the bank would have to sell off its Greek branch network and operations. When the directors refused to sign-off the deal that had been hastily arranged by the Central Bank of Cyprus the Governor, Panicos Demtriades, signed the agreement instead.

On Thursday 21st Laiki workers began protests as they heard that the bank was to be put into a resolution regime and run down. With time running out the

Cypriot authorities had just three days to put together a bank restructuring plan capable of winning troika approval and thus preventing the ECB from acting on its threat of cutting off Laiki

from its Emergency Liquidity Assistance (Reuters Noonan 2 April 2013).

Simon Cox The Bank that brought down Cyprus BBC World Service 'Assignment' aired 4 April 2013.

In this very useful piece Simon Cox traces the downfall of Laiki Bank to its takeover by the Greek company, Marfin Investment Group, in 2006. His programme argues that the bank's culture and practices changed from this time from a rather conservative retail bank to an 'investment bank mentality' as an un-named very senior executive puts it.

And although denied by the ex-Chief Executive of Laiki Bank, Efthimios Bouloutas, the same executive claims that the Cyprus 'side' of the bank (the bank's base was moved to Cyprus in 2006) did not have information the bank's total exposure to Greek coporate loans (outwith its exposure to GreekGBs) until 2011,

This only came to the surface in 2011 when all the credit committees were merged. So we looked into the loans and realised what was going on and said, 'What is this?' We had lots of arguments about it.

Asked by Cox about a €700m loan to a shipping company the same un-named executive says,

This was the biggest disaster. I think we lost €350m on that. But there were others for example. One of the TV channels in Greece had a loan of half a billion Euros.

This executive admits that mistakes were made but blames the downfall of the bank equally between the bank, politics and the Troika.

Cox then interviews by telephone Efthimios Bouloutas, Marfin Chief Executive and ex-chief executive of Laiki Bank. In the interview Bouloutas denies the assertion made by the executive above regarding the lack of knowledge held by Cyprus 'side' of the bankwith regard to the loan situation in Greece unitl 2011. He also says it is incorrect that Laiki was making loans in Greece with little collateral cover.

Asked about €400m of loans made to directors in 2011 Bouloutas says that these had accumulated over time and were not made in one year. He defends the loans by saying that they were all published and that they all had been approved by the Board of Directors.

Outside of the interview Cox says that financial documents he has seen 'clearly state that the Board of Directors and their connected people took loans of €400m' in 2011.

He finally asks Bouloutas about the €9bn of ELA loans that Laiki had. Bouloutas replies, 'In my view the political decision to [??? 20.40 mins into interview] Laiki is what led to the situation that you have currently.'

There is a crucial word here that I cannot make out.

Earlier in the interview Bouloutas refers to the European banking authority's stress tests of mid-2011 which were passed with 'flying colours' by Laiki and which were in his words, 'these were sole [ly?] indicators of the robustness of the Cyprus banking system.'

Earlier in the programme Cox speaks to an employee of the bank who reveals that Laiki encouraged employees to take loans - some as a big as €60-70,000 - to buy Laiki share. (The 60-70k figure is not in the Assignment piece but is in the lead to the broadcast in BBC WS World Business Report 3rd April 2013).

The employee tells Cox that she has both a mortgage with Laiki and outstanding loans. She used some of these loans to buy Laiki shares,

after directors of the bank over the years telling employees it would be nice, you know, if they could get a loan to buy shares in the bank and support in that way their employer; the bank that feeds them; that gives them bread every day.

And in another instance a director called us and put us in a small conference room telling us it would not look good on our resume if we sold those shares. So most people didn't sell their shares. In the meantime afterwards we found out that all the directors had sold theirs [even the director who had told them to hang onto them]. That person sold all his shares and even left the bank.

In the programme Cox also interviews Andreas Neocleous, founder and managing partner of Andreas Neocleous & Co LLC, Cyprus's largest law firm (see Wikipedia: Andreas Neocleous and Andreas Neocleous & Co). In the interview he says that his firm has lost 'a little bit more than €20m' through its deposits in Laiki Bank and the Bank of Cyprus.

A detailed piece by Reuters in June 2012 (Grey, Kambas and Leontopoulos 13 June 2012) found Laiki bank's new executives following the Cypriot state takeover of the bank in May 2012

have uncovered what they suggest is evidence of huge exposure at its Greek businesses to risky investments, including loans issued to investors who bought shares in the MIG conglomerate. They allege this has left the bank too vulnerable to MIG's fate.

The articles goes on to say that

A look at Marfin [later Laiki Bank] ... suggests that [Greece's] financial woes were exacerbated by conflicts of interest at some banks and by light regulatory supervision

of them.

Laiki lost €2.5bn through its exposure to the Greek sovereign haircut but it was also massively exposed to other loans in Greece.

Of its capital shortfall, the bank estimates nearly one-third arises from provisions for bad loans in Greece. According to [Michalis] Sarris [the new non-executive chariman of the bank in June 2012], the "single most important factor" dissuading investors from helping recapitalize the bank was now not sovereign bonds but concern that further losses in Greece could materialize.

"We now have a loan portfolio in Greece of about 12 billion and funding of 6 and 7 (billion euros)," he said. The gap has to be financed by Cypriot depositors.

"Purchases of shares were made with loans, which in and of itself is not a very good practice," said Sarris. The risk was compounded by the fact that the loans were mainly secured with the very same shares. This made the collateral shaky, because stock prices can drop. "It is even less wise when (the) companies that do that are related."

"There is a lot of smoke, which means there is some fire," Sarris said. "But how much of it, and to what extent can it be justified, I am not sure."

In June 2012 Laiki bank was considering selling its two Greek subsidiary banks, Marfin-Egnatia and the Investment Bank of Greece, and their

extensive branch networks.

The larger Marfin group had huge ambitions in 2007 announcing it was seeking to become one of Europe's largest biggest business groups with a market capitalisation of €140bn within five years.

But within two years it was mired in a corruption scandal.

Greek investigative journalist Kostas Vaxevanis showed how the Vatopedi monks of Mount Athos,

had engaged political help to obtain the rights to a nature reserve in northern Greece and then, with more help, to swap it for valuable state-owned real estate across the country. The monks were also major players on the stock market and received 109 million euros in loans from Marfin bank.

A special inquiry on Vatopedi in 2010 heard the monks spent 30 million euros they borrowed from Marfin bank, the monastery's biggest lender, to buy shares in the MIG rights

issue, plus another 42 million euros in other investment schemes with MIG or its associates.

Further enquiries by regulators in Greece and Cyprus of Marfin-Egnatia in

March 2009 found that the bank had been undertaking risks

"whose level and nature provoke concerns to the supervisory authorities regarding their correct and adequate management". Loans from Marfin to the MIG group suggested "favorable treatment" while "the relationship between MPB group and MIG group creates the impression that the close ties between the two groups played a significant role in the approval of those loans."

By 2011 relations between the Cyprus Central Bank and Laiki Bank had become poisonous. In November Vgenopoulos quit as Marfin's chairman, just as Central Bank of Cypurs Governor Orphanides was preparing to ask him to resign on the grounds that he was responsible fora liquidity crisis

A month later, chief executive Efthimios Bouloutas was sacked on the instruction of Orphanides, who has not publicly said why.

In April 2012 Orphanides stood down from the Cypriot Central Bank after the government opted not to renew his five-year term. In his few remarks on his term in offices he has,

accused Cyprus's ruling communist government of siding with Vgenopoulos and opposing more stringent banking regulations. "It saddened me to be the recipient of political interventions which in all cases were to relax the supervisory framework or meet certain interests," he told parliament.

Vgenopoulos has in turn accused Orphanides of acting improperly and denied any wrongdoing during his tenure at Marfin bank and as chief executive of MIG.

Bank of Cyprus

When Laiki bank was being merged into Marfin in 2006 Bank of Cyprus launched an ambitious takeover bid for a Greek bank, Emporiki Bank, that was pipped at the post by a rival bid from France's Creit Agricole.

The failed bid led to a shake up at the bank with departures from the board. The chair Vassilis Rologis resigned and within management younger bankers moved into senior positions.

Having achieved a big reduction in costs in its Cyprus operations while increasing its 9 monthly profits in 2006 by 160% to €226m the bank had its eyes on expansion into Russia and Romania (see FT Hope 19 December 2006)

Archbishop Chrysostomos, head of the island's Orthodox church, is actively involved in the Bank of Cyprus and the church controls a 5 per cent stake of the bank. (FT Hope 2 February 2007).

Employs 11,000. Valued €7.5 billion end 2007. Dropped to €400 million March 2013. Largely retail banking in Cyprus and Greece, some investment banking, private banking and hotel interest in Ayia Napa.

Deposits: Only 10 percent of Bank's €27.8 billion of deposits in units outside euro zone. The Russian and UK units of Bank of Cyprus hold a roughly equal amounts at 1.2 billion euros each. Cyprus deposits 66 percent total, Greece 23 percent (end-September 2012 data). Loans: Cyprus (52 percent), Greece (33 percent), and the rest Russia, Romania, Ukraine, Channel Islands (Reuter Noonan 23 March 2013).

The owners of Bank of Cyprus: 61 percent of its shares were owned by Cypriots and another 13 percent by Greeks in 2011. In trouble because the bank lost €1.6 billion on Greek government bonds in 2011. in 2012 provisions for bad loans more than doubled to €800 million as bad loans ratcheted up to 17 percent of the total loan book. Greece was the source of 2012's loan losses with €436 million of provisions allocated there.

The Bank of Cyprus (not to be confused with the island's central bank) announced it needed €500m to make up its capital requirements (Cyprus Mail 28.6.2012).

The chairman, Theodoros Aristodemou, a property developer and the bank’s largest private shareholder resigned in late August 2012 (FT Hope 29 August 2012) Wednesday, only weeks after the chief executive 'was forced to stand down' after revealing an unexpected €500m capital shortfall.

The chairman cited health reasons in a letter to the bank’s board announcing his resignation.

An article in the New York Times (31 March 2013) details the way in which BoC withdrew from Greek bonds in 2009 only to plunge back into the market from December 2009 to June 2010 in what the article claims was in essence a bet on the difference between the buying price for the bonds at 70 cents in the Euro and the loss on the bonds when that occured. The paper quotes a Cypriot banker familar with the transactions

“This was pure speculation — European banks like Deutsche Bank were desperately trying to get rid of these things.”

When Greek bonds were written by 75% in March 2012 BofC lost €1.6bn - 4.4% of its assets.

The FT has drawn attention to problems with Bank of Cyprus's Russian subsidiary Uniastrum, 'where non-performing loans are more than 25 per cent higher than the average for the country' (FT Jenkins/Hope 19 March 2013).

Interestingly Fitch, the rating agency, reasons for the BB+ to BBB- downgrade of Cypriot sovereign debt on 2012 were in part down to the deteriorating position

of Cyprus's banks in Greek corporate and household markets.

‘This is principally due to Greek corporate and households exposures of the largest three banks, Bank of Cyprus, Cyprus Popular Bank (CPB) and Hellenic Bank and to a lesser degree the expected deterioration in their domestic asset quality.’ (Fitch quoted in FT David Keohane Blog 25 June 2012 - see also FT Hope 22nd March 2013 for the reckless expansion of Laiki).

Some small savers (17,000 of them in total) who invested in the PBC and BofC convertible bond issue above (posting a return of 7%) protested outside the BofC's HQ at the end of January 2013 as threats emerged that they might be sacrificed as part of a haircut on the banks' creditors as part of the EU bailout of the banking sector (see FT Jan 31 2013).

There protests were in vain. They were sacrificed.

(This is very similar to the fate of Bankia customers/investors in Spain – who’s shares were recently written down to €0.01 after being aggressively sold the shares as savings account equivalent risks (see FT Buck 22nd March 2013).

Depositors with over €100,000 at the Bank of Cyprus will get shares in the Bank in exchange for 37.5 % of their uninsured deposits and 22.5 % of those deposits will be put into fund with no interest which could see more write downs as the Bank's bad debts are sorted out (see FT Jenkins and Stothard 2 April 2013). The other 40 per cent will be unfrozen “in a short period of time.” Bank of Cyprus share prices fell over 95% over the last two years and the bailout has wiped out their residual value (FT Lex 31 March 2013).

The UK operations of Bank of Cyprus had 50,000 customers with deposits of £920m - largely in tax-efficient individual savings accounts - in June 2012 when it joined the UK's deposit guarantee scheme. It had been offering one of the best interest rates - at 4 per cent - on the market to attract depositors. UK Bank of Cyprus depositors will not suffer a haircut on deposits over €100,000 (£85,000) (FT Moore 6 and 8 June 2012).

THE former CEO of the Bank of Cyprus, Andreas Eliades, who resigned in July 2012, recently claimed that certain circles in Cyprus, inside and outside BoC, not only failed to join forces but undermined every effort to tackle the crisis.

“Unfortunately, developments confirmed that it was all part of a well-devised plan to break up the entire banking sector and especially the Bank of Cyprus, which was in good financial condition

at the time.” (see Cyprus Mail 3 April 2013).

B of C also has €1bn ELA allocation which broought total Cyprus allocation to just over €10bn. B of C now has all that €10bn on its balance sheet ( the Laiki €9bn was passed over to B of C as part of the resolution process) and this brings it 'close to the ECB acceptable threshold' according to The Scotsman (Melvin and Baetz 25 March 2013).

The Alvarez and Marsal Report: 'a desperate and dumb bank'

In August 2012 the Cypriot central bank commissioned Alvarez & Marsal, a financial restructuring firm, to investigate the Bank of Cyprus's high-risk investment strategy of buying billions of euros of Greek government bonds between December 2009 and June 2010 which resulted ina loss of €1.9bn. The report surfaced on 4 April 2013.

Alvarez investigators said that, according to the records they were able to secure from the bank, the decision to buy the bonds was based on a last gasp effort by the bank to generate profits as their loan book began to sour in late 2009 and through the spring of 2010.

The investigators also discovered that the bank made use of cheap financing from the European Central Bank to make these bets. 'As a result, executives in the bank’s treasury department bought the riskiest high-yielding bonds available and found willing sellers in banks eager to reduce their exposure to Greece.'

This is remarkable. The report suggests that Bank of Cyprus massively invested in GGBs, when everyone else was getting rid of them, because its loan book was 'beginning to soar'. So losses building up in one part of the bank were offset by a huge gamble in another. That did not work. And that gamble was funded by cheap financing from the ECB - no wonder they were pissed off. And then executive are alleged to have covered their trail by deleting documents from bank computers.

The findings of the Alvarez report, especially the contention that top bank executives may have obstructed a central bank investigation, are likely to stir anger widely in Cyprus.

The issue of how the banks became laden with Greek government bonds has become an explosive one in Cyprus as politicians and regulators try to explain to furious taxpayers why the country has been forced to impose harsh measures on bank clients of all sizes, including restrictions on fund transfers and withdrawals.

(For above see NYT 4 April 2013).

Joseph Cotterill in the FT Alphaville blog (April 5 2013) analysed the same period using leaked portions of the report. He wrote that it showed 'how a desperate and dumb Cypriot bank' used the ECB's December 2009 Long Term Refinancing Operation to carry out 'a massive, abusive carry trade'. This they did by borrowing low from th ECB and earning high from Greek government bonds that no-one else wanted.

How was it possible for this trade to go undetected? The report says that the supervision department of the Cyprus Central Bank was 'potentially under-resourced, both in terms of numbers and experience of staff' and that the Bank of Cyprus's reporting periods for Sovereign Debt would have meant that CBC was informed of the huge increase in GGB holdings between December 2009 and March 2010 after the event.

(See also FT Hope 5 April 2013).

More from Alvarez and Marsal

Reuters reports 30 April 2013 on further revelations leaking from the A&M report on the Bank of Cyprus's disastrous bet on Greek government bonds.

The report, which Reuters has seen, alleges that bank executives may not have revealed details of bond purchases to board directors, avoided showing losses on the bonds, and may later have delayed external investigation of the bond purchases.

In this wonderfully detailed article many previously unkonwn aspects of the Bank of Cyprus's purchases of and accounting for GGBs are revealed.

As investors' fears over the solvency of Greece grew, the value of the Greek bonds fell. The Bank of Cyprus made changes to the way it accounted for the bond holdings, according to the Alvarez and Marsal report, with the result that the growing potential losses were not spelled out to investors.

In April 2010, it moved about 1.6 billion euros of Greek bonds from its trading account to its "held to maturity" book. This meant the bank did not have to mark down the value of the bonds.

The article also details the alleged cover-up by wiping email traffic from one of the bank's computers.

Piraeus Bank and the fate of Cypriot branch networks in Greece

The Greek bank, Piraeus Bank, (FT Hope 22 March 2013) bought up the Greek operations of Cyprus Popular Bank (Laiki), Bank of Cyprus and Hellenic Bank, as well as the Investment Bank of Greece (IBG), a Laiki subsidiary – in all 312 branches - for €524m (Ekathimerini 27 March 2013).This was done under duress and as a dictat from Cyprus's Central Bank.

Hugo Dixon at Reuters calculates the assets were sold at 19% of their net asset value. €15bn of deposits were also transferred with the Greek branches and there was no haircut on the uninsured deposits over €100,000. Instead Cypriot non-insured deposits have had to bear the whole burden of the bail-in,

exempting Greek deposits from the bail-in meant that the Cypriot ones had to shoulder the whole burden instead of only 63 percent of it.

Piraeus expects to close half of its expanded network of 1,600 branches (FT Chaffin 26 March 2013).

Piraeus Bank was a direct beneficiary of the EU recapitalisation of Greek banks in May 2012 and received €4.7bn bonds from the European Financial Stability Fund via the Hellenic Financial Stability Fund in May 2012 (FT Hope 28 May 2012).

These bonds were designed to act as collateral which would allow the banks involved to regain access to the ECB’s liquidity operations at cheaper rates than under the emergency liquidity arrangement. This mechanism was denied banks in the Cyprus bailout.

The Greek finance ministry also pledged to inject €1.5bn of new capital into the combined Greek operations of the Laiki and BofC banks before they were taken over by Piraeus Bank (FT Hope 22 March 2013).

A press relase from Piraeus Bank of 26 March 2013 states

Piraeus Bank signed an agreement today to acquire all of the Greek deposits, loans and branches of Bank of Cyprus, Cyprus Popular Bank and Hellenic Bank including loans and deposits of their Greek subsidiaries (leasing, factoring and the Investment Bank of Greece) for a total cash consideration of €524m.

Reuters (26 March 2013 Georgiopoulos, Papadimas and Noonan) reported that the deal was funded by Greece's bank bailout fund HFSF - the Hellenic Financial Stability Fund.

Greek banks including Piraeus will themselves be recapitalised to shore up their solvency ratios. Most of the cash injection will be provided by a state bank bailout fund - the Hellenic Financial Stability Fund (HFSF).

Piraeus's capital needs have been estimated by Greece's central bank at 7.3 billion euros. The 524 million euros for the Cypriot acquisitions will be supplied by the HFSF in exchange for shares, an official at the fund told Reuters.

The €16.2bn net loans figure above includes 'expected losses determined by the review of international specialized firm.'

James Ker-Lindsey (Financial Mirror 3 April 2013) noted recently that Cypriots have been disappointed in the lack of solidarity from Greece:

It is telling just how many Cypriots seem to feel that Greece should have done more to try to help them, especially as it was the overexposure of Cyprus’s banks to Greece that was at the very heart of the crisis the island faced.

Depositor haricut exemptions

It should also be noted that the Cypriot authorities have exempted certain entities from paying the haircut at Laiki Bank and the Bank of Cyprus - these are the government, municipalities, financial institutions, insurance companies, schools, universities, charities and the country’s main credit card processing company (Hugo Dixon at Reuters 3 April 2013

As Dixon notes, resolution authorities have a right to be flexible but 'Cyprus hasn’t said why the groups it has singled out are worthy of special treatment'.

Co-operative banks rumours of haircut

Central Bank denies rumours that Cyprus coopperative banks will suffer haircut on deposits over €100,000 (FT Hope 5 April 2013).

Massive lines of people formed outside cooperative banks across the country seeking ways to either get their money out or divide their fixed deposit accounts into smaller ones of under €100,000 following the circulation of text messages claiming the government was about to impose a haircut on cooperative bank deposits.

Finance Minister Haris Georgiades yesterday confirmed that around €1.2 billion of the €10 billion [bailout funding] has been earmarked for the cooperative banks and societies to cover any possible recapitalisation needs.

(Cyprus Mail, Evripidou, 6 April 2006).

The European Stress Tests

Both Laiki and BofC were stress-tested bythe Committee of European Banking Supervisors (CEBS) in July 2010.

Gabriel Sterne in his July 2012 Exotix report (above - see Laiki Bank) quotes an

IMF report of August 2010 that looked at the tests,

The July 2010 EU-wide tress testing exercise coordinated by the Committee of European Banking Supervisors (CEBS) that was performed for two of the largest banks provides further comfort that banks will be able to withstand significant deterioration in the market environment. Both banks, Bank of Cyprus and Marfin Popular Bank, passed the tests, which required Tier 1 capital to exceed a hurdle of 6 percent.

Sterne comments that stress-stests are only useful if the 'paint the full picture'. These ones did not, in his opinion, because

this stress test, and subsequent ones, did not fully write down the value of GGBs throughout banks’ books (p.5).

However, once published it is difficult for the regulatory authorities to disavow them. They may also give reassurance to the directors of the banks being tested that their operations are indeed in order even if some voices in the bank are less convinced of this case.

Much has been subsequently made of the failure of eurozone stress-stests to reveal the parlous state of Laiki and Bank of Cyprus and they and the ECB have become a scapegoat for those seeking to displace the blame elsewhere.

The April 9th draft MofU suggested there may have been areas not picked up by the stress tests other than the banks' exposure to Greek bonds and loans. It said notes the exposure to Greek debt but focuses on 'home-grown' problems,

many of the sector's problems are home-grown and relate to overexpansion in the property market as a consequence of the poor risk management practices of banks.

Property has been a real issue compounded by,

the sensitivity of collateral valuations to property prices, and banks have used certain gaps in the supervisory framework to delay the recognition of loan losses, thus leading to significant under-provisioning (see Memorandum).

The Pimco Banking Study

Pimco, the investment group, was commissioned by a committee including Greek-Cypriot officials and the troika of the European Commission, the ECB and the IMF to do an audit of Cyprus's banking sector. It estimated that a a bailout of between €7bn and €10bn would be needed to cover the banks' latent losses. This figure was deemed controversial and the report was never officially published (see Cyprus Mail Psyllides 21 February 2013).

Some, see for example Fiona Mullen of Sapienta Economics in Cyprus, have argued that Pimco over-estimated Cypriot bank losses and thus inflated the needs of the bailout that followed and hence the size of the haircut on uninsured depositors.

In its audit Pimco also modelled for a halving of property prices over the next three years in Cyprus.

Taken together the impacts of the Greek sovereign bond haircut, the bad loans on their books and the impacts of a fall in real estate prices Pimco estimated that both Laiki and Bank of Cyprus would require €4bn to be sufficiently recapitalised.

The falls projected by Pimco were contested by The Cyprus Association of Valuers and Property Consultants who were under the impression, according to the Cyprus Mail, (21 February 2013) that Pimco had projected a property price fall in one year of 40%. However, even in prime property areas of Nicosia and Limassol prices have fallen by 20% of the last three years and in outlying areas this rises to a 30% fall. House prices in Paphos have fallen by 40% and in Larnaca by 25%.

Release of the PIMCO banking study

On Friday April 19th 2013 the PIMCO study was finally released. It is dated February 2013, comprises 103 pages and is called Independent Due Diligence of the Banking System of Cyprus. It is supposed to be availabe at the Central Bank of Cyprus but the link for final report on 19th April did not work. Press release and QA are working. Full report available at Cyprus Mail.

Recapitalisation shortfall

Its main and widely leaked conclusion is that the Cyprus banking system faces a capital shortfall, based on 2012 data and using assumptions of macroeconomic conditions that are now widly inaccurate, of between €6 and €8.9bn.

The Adverse Scenario in the report that results in the higher figure is based on a cummulative (three year compounded) drop in GDP between 2011-2015 of -7.3% and house price change of -23.8%.

The draft Debt Sustainability Analysis of 9th April 2013 prepared by the European Commission estimates a fall in GDP in the period 2012-15 of -15.2%.

On April 4 the Cyprus government's spokesperson, Christos Stylianides, said,

“In 2013 the recession may not be 8.7 percent as is estimated, it may reach 13 percent.” (ekathimeri 4 April 2013).

Here are the year-on-year GDP forecast figures compared for the Debt Sustainabillity Analysis (see Memorandum) and PIMCO adverse and base macroeconomic scenarios.

DSA and PIMCO GDP forecasts for Cyprus 2012-2015

| Cyprus GDP | 2012 | 2013 | 2014 | 2015 | |

| DSA (Apr 2013) | -2.4 | -8.7 | -3.9 | 1.1 | |

| PIMCO ADVERSE (Feb 2013) | -2.1 | -5.2 | -2.3 | 0.0 | |

| PIMCO BASE (Feb 2013) | -2.1 | -3.0 | -0.6 | 0.8 |

|

|

||

Before leaving these now obsolete figures behind it is interesting to see how they are divided between domestic, foreign and cooperative banks. Of the €8.9bn shortfall €8.2bn is accounted for by domestic banks, €149m by the foreign banks and €589m by the coops p.19.

The overview of the banking system provides some useful information

Assets at €100bn are made up of 68 per cent loans and 13 per cent cash.

Liabilities of €94bn are made up of 71 per cent deposits and 15 per cent central bank. The report says that the total amount owed to the EU is €14bn made up of normal ECB funds and ELA - that is over 20% of the funding of participant institutions (p. 14).

Ends

Of net loans of €68bn 62 per cent are based in Cyprus, 29 per cent in Greece and 9 pr cent elsewhere.

Of €67bn deposits 60 per cent originate from outside Cyprus as either Greek (19%) or Russian, other or UK (7%) or as Cyprus non-resident deposits (34%). The other 40 per cent of deposits are Cyprus resident deposits.

(These figures are of course before the fire-sale of Cypriot bank Greek operations.) It is interesting to note that while 29% of loans were in Greece only 19% of deposits came from that country.

The report lists its summary and significant findings.

The summary findings conclude that

- loans are consdervatelly made on assets as collateral rather than on ability to pay,

- that it typically takes 10-12 years to recover assets - ie a forced house sale,

- that the identification of bad loans can be hampered by complex cross-collateralisation,

- that there is little incentive for borrowers to keep up payments because there is no immediate consequence when they are missed,

- there is a tendency to reshcedule rather than to aggresssively resolve loans

- unpaid interest is often reflected as accrued interest in balance sheets based on optimistic forecasts of eventual loan resolution through asset disposal,

- the above practices have been tenable in times of relatively fast property price rises but in times of collapsing real estate values they present a major problem in terms of - my words - chronic under provisioning and forecasting of bad loans. To paraphrase loan recovery is based on a never-never rescheduling into a future of rising house values and consensual asset disposal.

- transaction revenues for offshore banking services provide a critical component on non-interest revenues for the island's big banks.

- This flow of revenue is reliant on tax optimisation strategies and the report expects the level of demand for these sdrvices to remain high independent of macroeconomic conditions on the island, thus providing important stabilisation in the scenarios presented. (The increase in corporate and other taxes may have a disastrous impact on this trade.)

- lending traditions in the cooperative sector have been lenient and encouraged a culture of non-payments and payment holidays justifed under the rubric of the 'social function' of the cooperative ethos. Non-performing loan levels are higher than those at many Cyprus banks and provisioning is woefully low. Again rising property prices have tended to hide these defects but not any more.

Significant Findings

Loss absorption

- loss absorption capacity has been low due to poor provisioning for 90 day debts,

- the system is particularly reliant on non-resident deposits (nearly 50%) that are in turn attracted by low corporate interest rates and other tax incentives. A change in these is predicted to have a 'significant impact' on the level of funding in the system,

- there are relatively few alternative funding sources other than deposits and this has resulted in a major reliance on normal and emergency EU-type loans that constitute 20% of the system at a total of €14bn,

- there are signifcant levels of deferred tax assets and non-cash interest (which left me stumped!).

Loan loss analysis

- High rates of NPLs have been covered by high loan cure rates and collateral - falling property prices will adversely impact on these,

- the model of lending leads to high probabilities of default but low loss severities - because in a system of risng property values carried-over loans and accrued interest are usually and in the medium-term paid off, particularly as loans are often spread between a network of borrowers and third party guarantors,

- The corporate sector in Cyprus and Greece is highly leverage resulting in high default probabilities,

- Some of the largest exposures at participating institutions were made to affiliates of the instutition where loans were made to offshore vehicles that then bought shares in the loan-issuing institution. These resulted in higher than average losses.

Cooperative banks

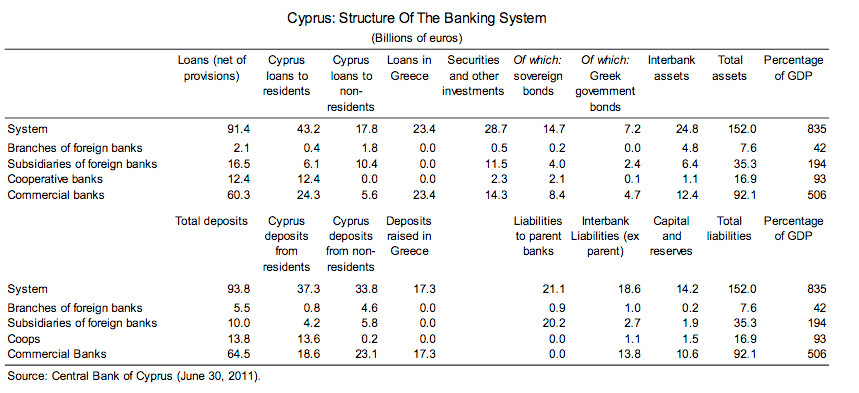

The main cooperative bank is the Co-operative Central Bank. The table at the top of this page shows that Cyprus' co-op banks take deposits from (€13.6bn) and lend (€12.4bn) to Cypriot residents almost exclusively. They have no exposure to Greek loans or sovereign debt but hold €1.9bn of Cypriot sovereign bonds. Their assets are rquivalent to 93 per cent of GDP IMF Cyprus Selected Issues 2011. 27 per cent of their loan book was 90-days in arrears.

the existence of the cooperative banking (or co-ops) sector consisting of a large number of locally active “mini” banks all brought together under a mutual cross guarantee system under the Co- Operative Central Bank. This sector, with its close ties with the government, presents an altogether different stability issue (p.132)

Clerides, M. (2011) Discussion on Banking System in Cyprus: Time to Rethink the Business Model?, Cyprus Economic Policy Review,5:2

A review of of Costas Stephanou Improving the Stability of the Cyprus Banking System”

That ELA loan (Emergency Liquidity Allocation)

The €9.2bn ELA loan forced upon its main bank will likely cause it to sink, potentially bringing down the banking system. The resulting loss of confidence will not only destroy the local economy, it will send systemic ripples across the global financial system.

Lenos Trigeorgis, Professor of Finance at the University of Cyprus in FT 8 April 2013 Economists' Forum

Central Bank of Cyprus: allegiance to whom?

Mpersianis writes about the ambiguity inherent in the position of national central banks. Their governors sit on the board of the European Central Bank and as such can become part of the ECB/IMF/European Commission applying bailout conditions to their own country. To whom does a national central bank owe its loyalty?

Treaty legislation and roles and responsibilities covering the ECB and the European System of Central Banks

Actually the position of NBC - national central banks - is very clear within EU treaty legislation.

The ECB was set up in 1998

The European Central Bank was established on 1 June 1998. It has legal personality and is fully independent of national and European institutions. The ECB ensures the smooth running of the Economic and Monetary Union by managing the European System of Central Banks (ESCB). Its primary objective is to maintain price stability by defining the monetary policy of the Union.

ACT

Protocol on the Statute of the European System of Central Banks and of the European Central Bank annexed to the Treaty on European Union and the Treaty on the Functioning of the EU [Official Journal C 83 of 30.3.2010].

The European System of Central Banks (ESCB)

The ESCB is made up of the European Central Bank and the national central banks of the Member States. The ESCB's principal aim is to maintain price stability within the EU by way of:

- defining and implementing the monetary policy of the Union;

- conducting foreign-exchange operations of the euro vis-à-vis national currencies;

- holding and managing official foreign-exchange reserves of the Member States;

- promoting the smooth operation of payment systems.

All above from europa.eu here

See below from ECB Website here

The operational set-up of the Eurosystem takes account of the principle of decentralisation. The national central banks (NCBs) perform almost all operational tasks of the Eurosystem. In doing so, they enact the decisions made centrally by the Governing Council of the ECB.

The NCBs are responsible for

- Execution of monetary policy operations: this means that the NCBs carry out the actual transactions, such as providing the commercial banks with central bank money.

- Operational management of the ECB's foreign reserves: this includes the execution and the settlement of the market transactions necessary to invest the ECB's foreign reserves.

- Management of their own foreign reserves: planned NCB operations in this area are subject to approval from the ECB, if such transactions could affect exchange rates or domestic liquidity conditions and if they exceed certain limits established by ECB guidelines. The aim is to ensure consistency with the monetary and exchange rate policy of the ECB.

- Operation and oversight of financial market infrastructures and payment instruments: NCBs act as the operators of the national component systems of TARGET2, the payment system for the euro, and its respective national user community is thus able to participate in TARGET2. Some NCBs also operate securities settlement systems. Furthermore, NCBs are involved in the oversight of financial market infrastructures.

- Joint issuance of banknotes together with the ECB: both the ECB and the NCBs are issuers of euro banknotes. All banknotes are put into circulation by the NCBs, which accommodate any demand for euro banknotes by launching annual banknote production orders and by operating a Eurosystem-wide stock management system. Both activities are coordinated by the ECB. NCBs take measures to achieve a high quality of banknotes in circulation and to analyse counterfeits.

- Collection of statistics and providing assistance to the ECB: the ECB requires a wide range of economic and financial data to support the conduct of its monetary policy and the fulfilment of other Eurosystem tasks. The main areas where the NCBs help by collecting data from the national financial institutions are: i) money, banking and financial markets; ii) balance of payments statistics and on the Eurosystem's international reserves; and iii) financial accounts.

- Functions outside the European System of Central Banks (ESCB): national central banks may also perform functions other than those specified in the Statute unless the Governing Council finds, by a majority of two-thirds of the votes cast, that these interfere with the objectives and tasks of the ESCB. Such functions are the responsibility of the national central banks.

The size of bank depositor losses mounts

From FT 10.4.2013 Peel, Hope and Terazono repport on Cypurs gold sale plans:

The document also shows that losses imposed on junior debt-holders and uninsured depositors in Cyprus’s two largest banks – a condition of the €10bn EU/IMF bailout – are now expected to raise €10.6bn rather than the €5.8bn originally envisaged.

Russian frozen deposits revealed

Two of Russia's biggest companies reveal the amounts of money they have frozen in Cypriot banks. OAO Sovcomflot, Russia's biggest shipping group (revenue $1.4bn) has $25.8 million frozen in Laiki Bank.

And Russian auto maker AvtoVAZ has $20.5 million) frozen in Cypriot banks—about 40% of the company's 2012 profit. (WSJ Paris and Alpert 15 April 2013)

Why did depositors keep their money in Laiki and Bank of Cyprus as the situation deteriorated?

Fiona Mullen Financial Mirror Blog 6 March 2013 suggests Cyrpiot deposits were repratriated in the 2000 for a number of reasons,

Cypriot deposits were attracted home by the lifting of foreign exchange controls in 2002-04, the tax amnesty in 2004, the greater feeling of security against possible moves by Turkey brought on by EU membership in the same year and euro adoption in 2008.

But this does not explain why the 'vast majority of the €43 bln domestic deposits ... held by locals' did not leave the banks as signs of trouble grew. Mullen suggests a lack of alternatives, other than land (and presumably property).

Plus a lack of competition and high interest rates on deposits made the two big banks the natural resting place for many Cypriot's savings.

And since the competition commission is toothless, just two banks dictate how finance is raised, namely at high lending rates (and equally high deposit rates, which also reduces the relative attractiveness of other investments).

It might also be suggested that the large sums of money in the banks also reflected Cyprus's low taxes and poor social protection and health services. Instead of buidling an effective welfare state private indivuduals and households are left to fend for themselves. The trouble is once over the deposit insurance limit those savings start to become vulnerable.

The possibility of a haircut on both insured and uninsured deposits had begun to leak from the Troika in January 2013 and made the front page of the FT in February 2013.

We don't know yet how much money actually left the banks in the run up to the 15th March 2013 meeting of the Eurogroup of Finance Ministers with the Cypurs negotiators. But it is surprising that at least one big law firm and two large Russian concerns did not get their millions out of the country before the crunch came.