IV. Copper in Cyprus

Copper has been critical in the history of Cyprus - the Greek name for the ore - kupros - comes from the word Cyprus. A Cyprus Museum display (now disappeared) estimates that 200,000 tonnes of copper ingots were extracted by ancient workings from the Troodos ore deposits.

The charcoal required to extract the ore and purify it into the fantastic ox-hide shaped ingots produced for export was, it is estimated, equivalent to 16 times the entire wooded potential of ancient Cyprus - known as the ‘green isle’ for its bounteous forests of pine, cypress, cedar, and oak.

Thus, the fecundity of the island’s soil and rainfall had managed to regenerate the forests for thousands of years as different civilizations from the Chalcolithic – 'stone/copper age' – through Cyprus’s three bronze ages, and the Archaic and Hellenic and Roman – had taken their fill of the islands abundant metal.

(But see also here my page on the emergence of locust plagues from the fourteenth to twentieth century and the implication of deforestation as a possible cause for this.)

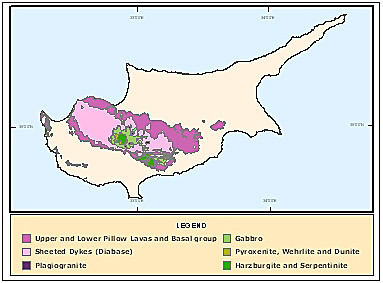

The copper belt in the Troodos is part of the Troodos ophiolite (oceanic crust).

It was formed in the Upper Cretaceous (90 Ma) on the Tethys sea floor, which then extended from the Pyrenees through the Alps to the Himalayas. It is regarded as the most complete and studied ophiolite in the world.

It is a fragment of a fully developed oceanic crust, consisting of plutonic, intrusive and volcanic rocks and chemical sediments. The stratigraphic completeness of the ophiolite makes it unique.

It was created during the complex process of oceanic spreading and formation of oceanic crust and was emerged and placed in its present position through complicated tectonic processes relating to

the collision of the Eurasian plate to the north and the African plate to the south (See Cyprus Geological Survey Department).

The copper ores had been laid down during sea floor spreading 90 million years ago in the Upper Cretaceous. It is now believed the copper was formed when vents from the deep below the ocean - black smokers - ejected millions of tons of super-heated water rich with dissolved minerals. These were then concentrated by the effect of water percolating through overlying limestone and forming hydrochloric/sulphuric acid that had dissolved the copper ores and redeposited them in thin, very rich seams.

The copper belt occurs in the pillow lavas laid down during sea floor spreading.

Copper is still being mined on the island at the huge Skouriotissa mine. Hellenic Copper Mines, which runs the mine, announced in April 2012 that it had produced over 50,000 tonnes of copper (see Western Troodos III). Copper Investing News 2011 says,

In 2010, around US$13.1 million worth of copper was exported from the mine. The majority of the copper produced in 2010 came from the processing of waste material from previous mining operations. In the past, only the richest copper deposits were exploited, now, given the new technology and economics behind the copper market, there is a point in revisiting some of the material left behind. In addition to reprocessing previous waste material, Hellenic copper is looking into reopening some of the mine’s ancient pits.

Given the current high price of copper there is renewed interest in exploiting Cyprus' remaining copper resources.

The first copper artifacts made on Cyrpus date from as far back as 4000 BC. The word 'copper' comes from the Latin Cyprium aes, the term used by the Romans for copper from Cyprus. These were made from native copper that would not have required mining. The first smelted copper dates from 2500 BC and was made using arsenic rather than tin as an alloy. Tin alloyed copper (ie bronze) was not made until 1900 BC and did not become predominant over the use of copper until 300 ears later.

Most early bronze and copper objects were either weapons or tools. It was not until the late thirteenth and mid-twelfth centuries BC that a technical revolution in copper and bronze techniques occurred, probably imported by crafts people from Mycenaean Greece and the Middle East.

The new techniques included elaborate work in sheet metal to make vessels, the use of two-part moulds, lost-wax casting and the use of hard soldering to assemble complex structures from different pre-cast pieces of copper or bronze.

Copper was one of the ‘principal attractions’ of Cyprus to Ptolomaic and Roman rulers. Under the Ptolomies an anti-strategos (lieutenant general) was appointed from Egypt and put in charge of the island’s mines. Cypriot bronze work was ‘indistinguishable from that produced elsewhere in the Mediterranean world’ in this period. Roman copper production was carried out by contractors under the control of a Roman procurator. (see Tatton-Brown, pp.30-35)

On his walking tour of Cyprus Colin Thubron arranges to see the huge opencast copper mine at Skouriotissa. The miners are constantly coming across Roman mine galleries that penetrate the earth to up to 600 feet. Galen, physician to Marcus Aurelius visited the mines in AD 166.He wrote:

At the bottom of the mine the smell of the air is suffocating and is tolerated with difficulty, being redolent of chalcitis and the rust of iron. The water has a similar smell.. The nude slaves carry the jars with the greatest of haste not to remain long in the mine. There are lights at moderate intervals, but they become extinguished frequently...It sometimes happens that a caving of the ground kills all the men, blocking the passage.

Journey into Cyprus, p.66

There is evidence to suggest that copper was initially smelted into rough products - bars and ox-hide ingots - close to the mines. This was then transported for further refinement and working to the coastal settlements.

A foundry hoard was found by a British Museum expedition at the ancient settlement of Enkomi - just behind the later settlement of Salamis - at the then mouth of the Pediaios river on the east coast of the island.

The hoard consists of foundry workers' tools - charcoal shovels, sledgehammer, furnace spatulae, tongs, scales; carpenter's tools, raw bronze products including a 36kg oxhide ingot, bits and pieces of other bronze products to be recycled, including jets from previous casting, and a pair of bronze ten-spoke wheels.

A clay tablet in the British Museum dating from around 1375 BC in Upper Egypt from the King of Alashiya, thought although not proven to be Cyprus, to the King of Egypt, apologies for the small quantity of copper sent to the King due to the 'hand of Nergal' (possibly pestilence that has slain all the copper workers). This suggests the great importance of the copper trade to ancient Cyprus.

The beautiful so-called Chatsworth Head - because bought by the Earl of Devonshire and once displayed at his seat at Chatsworeth House in Derbyshire - which probably depicts Apollo was found at Tamassos in 1836 and is believed to date from 460 BC. It is now in the British Museum and a copy stands at the entrance to the Cyprus Museum in Nicosia.

A hollow cast bronze leg, possibly from the same statue as the Chatsworth Head is held in the Louvre in Paris.